5. Patient involvement in different phases of HTA

| Site: | EUPATI Open Classroom |

| Course: | Patient Involvement in HTA |

| Book: | 5. Patient involvement in different phases of HTA |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 1 July 2025, 6:24 AM |

Description

Section Overview

- 1. Patient involvement in different phases of HTA

- 1.1. Forming the HTA questions: Policy and HTA

- 1.2. Exploration of patient aspects

- 1.3. Patient input in HTAs

- 1.4. Providing evidence on patient aspects

- 1.5. Evaluation of questionnaires

- 1.6. Evaluation of PRO and HRQoL instruments

- 1.7. Evaluation of qualitative research

- 1.8. Evaluation of effect endpoints

- 1.9. Interpretation of effect size

- 1.10. Evaluation of safety

- 1.11. Patient involvement in synthesising

- 1.12. Patient involvement in appraisals

1. Patient involvement in different phases of HTA

(This section is organised in the form of a book, please follow the blue arrows to navigate through the book or by following the navigation panel on the right side of the page.)

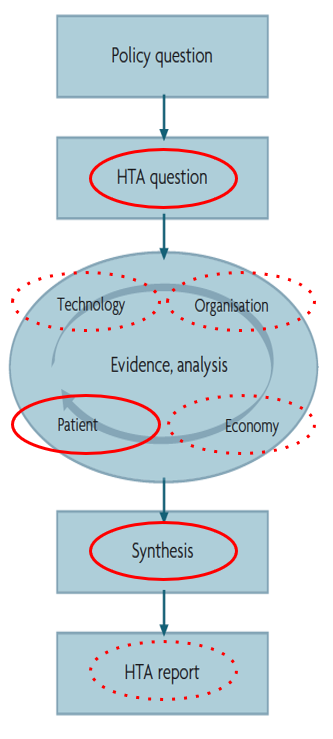

The below figure shows the simplified HTA process and where patients should have a prominent role (shown by solid lines) and where patients have a less prominent role (shown by dotted lines).

Figure 1 HTA process and patients’ role

Some HTA bodies have recently defined the patient perspective as one out of four pillars that should be evaluated:

- clinical effect and safety

- patient perspective

- health care organisation

- economy

This is seen as a both ethical and democratic requirement even though it does not diminish complexity in the HTA process. It is, however, noteworthy that the need for patient engagement and thorough understanding of the patient's perspectives, experiences, needs and preferences is gaining higher recognition by policy makers and HTA bodies.

As patient organisations become familiar with HTAs they are increasing their engagement in debates about policy priorities and access. And they influence HTA recommendations to inform action and lobbying to access new therapies or improve the usage of existing therapies.

Below is a list of various aspects where patients contribute [1,3,4]:

- Serving as members of HTA boards, committees, and workgroups.

- Identifying potential topics for HTA.

- Setting priorities among HTA topics.

- Identifying potential target groups for HTA reports early.

- Identifying health outcomes and other impacts (economic, social, etc.) to be assessed.

- Contributing to the development of instruments that measure what matters to patients (e.g., HRQoL).

- Reviewing proposals or bids by outside organisations/contractors to conduct HTAs.

- Providing expert input to an appraisal committee.

- Submitting evidence for HTAs.

- Reviewing draft HTA reports and recommendations.

- Helping to design and prepare patient-friendly HTA report summaries.

- Dissemination of HTA findings within patient groups, and other target groups.

- Evaluating the use of HTA recommendations.

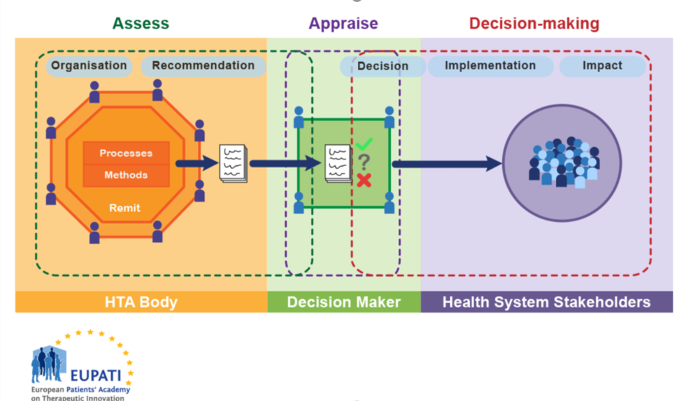

We can consider the entire HTA process as shown in Figure 2 below, which also outlines the different ways that patients can be involved in the full HTA, decision-making and implementation process.

Figure 2 HTA involvment in the health system

1.1. Forming the HTA questions: Policy and HTA

The formulation of the HTA questions is crucial for patients. The HTA questions will influence the choice of methods, assessment and synthesis. Therefore, it is important for patients to be included at this level. The formulation takes place in the light of the expected decision situation, i.e. based on the knowledge of decision-makers, target group and stakeholders. Patients should be part of the stakeholder group who formulates the HTA question. This ensures that relevant aspects important to patients will be included in the assessment.

In the case that patients are not involved at this step they can lobby for greater transparency, the opportunity to provide input through public consultation or being directly consulted before the formulation of the HTA question.

HTA bodies need to make judgements about the added value of a new health technology given the available information (data). Data in this context can range from clinical research to patient experiences. Assessments of data will take place in the form of either qualitative or quantitative research approaches. More information about research approaches you can find in HTA and Evaluation Methods Qualitative and HTA and Evaluation Methods Quantitative courses.

It is important to pay attention to research questions from previous HTA reports and other HTA literature and to avoid data simply being applied to the HTA project in question because the specific situation, target group, disease stage or other aspects may differ. Patients can critically evaluate whether prior HTA data is applicable to their current situation or require new evidence to be sought.

1.2. Exploration of patient aspects

HTAs have first and foremost been formulated on the basis of experts’ knowledge of a given health technology with the aim of providing the basis for political and/or administrative decision-making. A review of 50 HTA reports from eight countries over the period 2000 – 2005 has shown that clinical studies are usually taken as the basis when patient aspects are discussed – and not the actual effects related to the patient’s everyday life or treatment situation (10). This is in spite of the fact that the patient is the only one with direct experience of an overall course of events.

In recent years, it has become increasingly important to include patients’ own experiences, preferences, resources, needs, requirements and assessments in HTAs and to have local patients in different roles to ensure that the data and evidence assessed reflect the situation of patients on national and local level.

Patients can contribute to the HTA by producing knowledge from different perspectives:

- An individual perspective: Focus on the individual patient in relation to his or her everyday life

- A group perspective: Focus on a group of patients’ experiences and assessments of the effect of a given technology on their everyday lives

- A social perspective: Focus on patients as citizens, users, consumers and, for example, their assessment of how different technologies should be prioritized or what criteria should underpin the introduction of a specific technology.

At a more detailed level, this ensures that the following aspects are included in the evidence assessment:

- Patients’ knowledge and experiences of a given technology

- Patients’ preferences, needs and expectations of the technology

- patients’ visions and requirements concerning the technology

- Economic aspects and organization (impact on the individual patient)

- How customs, attitudes and traditions influence patients’ experiences, preferences, etc.

- What importance the technology has or may have for the patient’s everyday life

- How patients’ self-care and/or empowerment resources are best exploited

- And what opportunities and limitations apply to self-care/empowerment

For an HTA of high quality and transparency - and for decision makers to have a well-founded justification for their decision - evidence of above aspects must be produced and presented in a scientific way. Patients and organizations should therefore ensure that the people who represent them on boards, in committees and working groups have sufficient understanding of how to produce and interpret this kind of data.

The following sections provide recommendations for patients on when to provide input to the HTA and where to help defining, interpreting and synthesizing data that is most meaningful and relevant to them.

1.3. Patient input in HTAs

Patients' knowledge and experiences of, and attitudes towards e.g. illness, suffering, treatment and the health technology they are involved with are very much linked to everyday life and based on their own actual experiences and/or those of others close to them and on a shared everyday culture.

International HTA reports have for the most part regarded the “patient” as part of the health technology being assessed [6] but in recent years there is a tendency to deal with patient aspects individually. When exploring patient aspects it is often appropriate to address aspects separately from health technology, organisation and economic aspects. This can be done by incorporating results from different types of patient satisfaction surveys, investigations of patient preferences and/or qualitative studies of patient needs, desires and experiences.

|

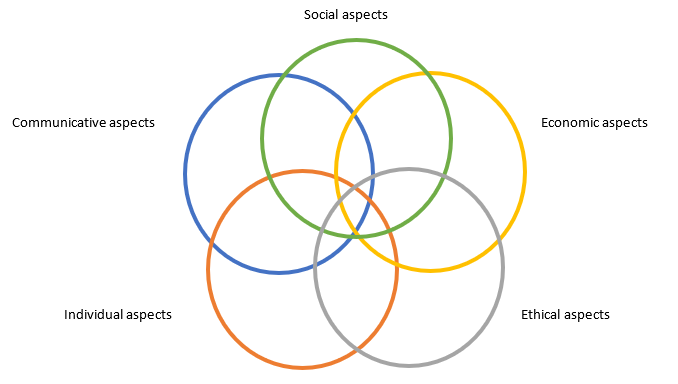

Figure 3 Patient experiences of a given health technology. Adapted after Kristensen [7].

The model shows that the various aspects should not be understood in isolation. However, from an analytical point differentiation is needed. Some examples of what one can choose to investigate within each area are set out below [7].

Social aspects: This covers whether, from a patient perspective, the technology will or has had, for example: a direct and/or indirect influence on/significance for work, family life, leisure time lifestyle/quality of life.

Economic aspects: This covers whether, from a patient perspective, the technology entails, for example: direct and/or indirect costs in relation to work, family life, leisure time, lifestyle, and quality of life.

Ethical aspects: This covers whether, from a patient perspective, the technology entails, ethical considerations, ethical choices, or ethical dilemmas.

Individual aspects: This covers whether, from a patient perspective, the technology entails: existential experiences, e.g. insecurity, worry, hope, anxiety, patient roles and stigmatizing, courage to face life satisfaction, use of one’s own resources (self-care, empowerment).

Communicative aspects: This covers whether, from a patient perspective, the technology will have or has an influence on: exchange of information, patients’ knowledge and understanding of the technology, modified relations between the patient and health professionals, and any potential positive or negative impact on involvement in decision-making about one's health.

Patients in HTA may help pointing to which relations between aspects are most relevant based on the specific national or local situation in which the HTA provides recommendations. Patients should be aware that even though valid evidence is available it may not always represent the situation in which they live themselves - and therefore a careful evaluation of the social, ethical and political situation is of high importance. This is where patients should critically evaluate the evidence that will be included in the assessment.

1.4. Providing evidence on patient aspects

There are numerous ways in which patients may contribute to the HTA discussions and the inclusion of relevant evidence of patient outcomes and impact on their life.

Patients can point to relevant and appropriate research methods to elicit, collect, and provide a basis to adequately evaluate patient outcomes, experiences and preferences. Patient perspectives may be very diverse. If patient perspectives are captured without systematic or agreed methodologies, the assessment may not reflect how treatments are valued by broader patient groups. This is where patients can point to and be part of developing, validating, and evaluating instruments and the way they are deployed.

In order for the HTA body to properly include the patient perspectives it is essential that patients who are involved in the process are able to understand the relation between the qualitative methods that explore patients’ lives (what is at stake, why is it important, implications) and how to further transpose these findings into numerical methods (how many, how much, for how long), and how comparisons or preference measures can be conducted.

Patients can contribute to the exploration and inclusion of patient relevant outcomes, health related quality of life and preference measures in several ways:

- Developing and/or validating patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). This helps regulators, HTA bodies and pharmaceutical companies to understand which concepts and domains should be measured during clinical trials and how, in order to get trustworthy HRQoL results (HRQoL is a Patient Reported Outcome, PRO).

- Evaluating PRO/HRQoL measures and the claimed changes (e.g., which concepts, domains, magnitude of changes) used in HTA. This may be important if the PROMs used in clinical trials which form the basis of many HTAs are not considered relevant by the patients who will be affected by the HTA-based decision.

- Endorsing certain PRO/HRQoL measures, both for clinical trials and other related studies (e.g., surveys).

- Developing, validating or evaluating patient preference measures including which relevant technologies and attributes to compare.

- Presenting patient experiences to HTA bodies – HTA bodies use information from such presentations and include this in the examination of the other data. For example, if patients consistently report that having a disease is burdensome because of the need to take a wide range of medications, HTA bodies will look at the data to see if a new medicine, or a new way of delivering a medicine, will reduce this burden.

- Providing patient–group submissions (for assessment) to HTA bodies in a format that allows the HTA body to look at impact across various decision criteria compared to current alternatives (such as equity, equality, legal, ethical, psycho-social). This ideally seeks to present information from a wide range of patients in a structured and unbiased way and may include all of the above elements or more. (See HTAi website for more relevant resources.)

1.5. Evaluation of questionnaires

Providing evidence on patient aspects: Evaluation of questionnaires

Evaluating questionnaires is one of the aspects where patients should have an important role.

Many PROMs are used repeatedly because they have been used in clinical research before and have gained a reputation as a standard questionnaire. This applies to both, disease specific or general questionnaires. Questionnaires should be considered instruments, and each component must be calibrated to precisely measure what it is intended for and to meet all other validity criteria (more about this you can find in this course). Too often, however, scientists fail to validate and calibrate these measurement instruments which means that they may no longer capture the most patient relevant concepts - or the options or scales used for answers may seem irrelevant to patients.

When reviewing questionnaires patients can consider the following [8]:

- Is the questionnaire appropriate in the context of the HTA question?

- Is the questionnaire validated - and by which criteria? Validity assesses to which extent the instrument measures what it claims to measure.

- Are all questions related to the technology of interest?

- Does the questionnaire measure what it is intended for with acceptable precision? This is especially important if the questionnaire was developed for a different purpose than the HTA question.

- Is the questionnaire adapted to the patient group - or subgroup of patients who will be affected by the HTA-based decision?

- Does the questionnaire go beyond what is considered acceptable by the target group?

- Are all questions understood by all readers in the same way?

- Are questions presented in an acceptable language and style?

For further validation criteria please see the HTA Course 4, HTA and Evaluation Methods: Qualitative.

1.6. Evaluation of PRO and HRQoL instruments

The traditional clinical outcome endpoints (often changes in mortality or morbidity, survival, risk or symptom reductions) are increasingly complemented by endpoints that focus on changes in the patient’s self assessed health status that occur as a result of a treatment. Assessment of patients’ health status, over and above mortality and morbidity, by instruments to measure patient reported outcome (PRO) or health related quality of life (HRQoL), is particularly relevant in an HTA context where a broad coverage of relevant elements is desirable.

Instruments for measuring health status may be disease-specific or

generic. The advantage of

using disease-specific instruments lies in their focus on a particular disease

and thus often greater sensitivity in relation to changes as a result of

treatment. For example, instruments have been developed for measuring health

status in relation to arthritis, chronic lung disease, diabetes and various

forms of cancer; other instruments measure single dimensions, such as pain or

depression. The disadvantage of disease-specific instruments is that they can

only be used in connection with the specific disease. They are unsuited to

comparisons across disease groups.

Generic instruments are those developed for use among a wide range of patient groups and diseases, and are therefore relevant for broader comparisons across disease areas. A disadvantage of generic instruments may be, however, that they are not sufficiently sensitive in relation to a specific disease and may not pick up changes that are relevant for the patient over time.

Using both types in the same study can be useful for an HTA because it makes comparison between elements easy. On the other hand many patients find generic questionnaires irrelevant because they may not capture the concepts and details that are most relevant to each specific patient group. Decisions on which PRO/HRQoL elements and results to include in an HTA may therefore have a crucial impact on patients.

In an HTA context, the assessment of changes in patients’ health and well-being form a central part of the assessment. Patients can play a role when considering below elements:

Study design: Many instruments have been developed to describe patients’ health status at a particular time, but may also be used to measure changes in health status over time. Patients can critically assess the instrument’s ability to measure the relevant changes over time in the disease of interest to the HTA.

Effect size: The effect size needs to be large enough to allow the identification of significant changes in health status meaningful to patients. Changes in PRO or HRQoL are seldom the primary endpoints because most studies are designed to test significant differences in clinical parameters. Patients can support HTA bodies in critically assessing whether the effect size considered in the studies really captures the relevant difference in health status.

Patient characteristics: These are crucial for the choice of health status instruments. Patients can critically question whether the instrument(s) is/are relevant for the characteristics of the patient population or whether a different version or another instrument should be used. The choice of instrument also depends on the disease status, purpose and domains of interest to the HTA, and of the extent to which different patient groups will be compared.

Method of data collection and analysis: While many instruments are intended for self-completion by the patient, the length or complexity of some instruments require a personal interview (incl. by telephone or video conference). Patients can critically question whether data collection has been conducted at times when clinically relevant changes in health status would be expected to be seen and how data was analysed and interpreted.

Sensitivity assesses how good the instrument is in picking up “meaningful” changes in health status over time – whether these are meaningful with respect to clinical decisions or the patient’s experience of health status changes. Patients can critically question whether "meaningful" has been defined in collaboration with patients.

Language and cultural aspects: Patients can also assess the acceptance of an instrument which is crucial for the success of the measurement and the instrument's level of language and literacy used. This is particularly important in languages other than the instrument’s original language where words may be correctly translated but miss the cultural context.

1.7. Evaluation of qualitative research

Providing

evidence on patient aspects: Evaluation of qualitative research

For assessing qualitative research in general patients can use the CASP Qualitative Checklist [9] which provides a number of questions for a systematic approach to evaluating qualitative research and why these aspects are important. The checklist is developed by experts in qualitative research under the Creative Commons license.

For the use of the checklist in an HTA patients can ask questions on whether:

- the research findings are relevant for the patient perspectives in the HTA of interest

- the patient population studied is representative for the local patients affected by the HTA-based decision

1.8. Evaluation of effect endpoints

Providing

evidence on patient aspects: Evaluation of effect endpoints

The effect of a health technology intervention is more than “efficacy”. Effect means how effective a treatment or the application of the technology is. In English there are two terms for effect: “efficacy” and “effectiveness”. “Efficacy” expresses the efficiency under ideal conditions, i.e. under research conditions such as clinical trials, whereas “effectiveness” expresses the efficiency under more normal daily practice. Patients can help define patient relevant elements to include in the assessment.

1.9. Interpretation of effect size

Providing evidence on patient aspects: Interpretation of effect size

Note: For more details about Statistics please see lesson Statistics in the Clinical Development module.

When assessing effect, patients should pay careful attention to how effect size is presented and statistical method in general. It is important information, as robustness of the statistical outcome is directly related to the statistical methods used as well as number of patients included in the study. Below sections provide a short overview of some of the commonly used ways of presenting effect and examples to illustrate what to pay attention to for non-statisticians.

Firstly, effect size measurements depend to a large extent on the endpoints designated in a study, for instance as difference in mean blood pressure (continuous endpoint) or difference in mortality (categorical endpoint). Secondly, effect size can be expressed in many different ways, depending on the focus of a study. For instance, the same quantitative effect can be presented , as relative risk reduction (RRR), absolute risk reduction (ARR), odds ratio (OR) or number needed to treat (NNT). The example in the table below shows the same effect as an odds ratio of 0.45, a relative risk reduction of 54%, an absolute risk reduction of 1.6% and number needed to treat of 62.

Calculation of different endpoints

Data from a randomized study

|

Treatment |

Number of patients |

Number of patients with effect |

Number of patients without effect |

|

4047 |

56 |

3991 |

|

|

Control |

4029 |

121 |

3908 |

Calculations based on data from above randomized study

|

Experimental event rate |

ERR |

56/4047 = 0.014 (1.4%) |

|

Control event rate |

CER |

121/4029 = 0.030 (3.0%) |

|

Odds for experimental events |

OE |

56/3991 = 0.014 (1.4%) |

|

Odds for control events |

OC |

121/3908 = 0.031 (3.1%) |

|

Odds-ratio |

OR = OE/OC |

0.014/0.031 = 0.45 |

|

Relative risk reduction |

RRR = 100x((CER-ERR)/CER) |

100x((0.030-0.014)/0.030) = 0.539 (54%) |

|

Absolute risk reduction |

ARR = CER-ERR |

0.030-0.014 = 0.016 (1.6%) |

|

Number needed to treat |

NNT = 1/ARR |

1/0.016 = 62 |

The same quantitative effect is expressed as an odds-ratio of 0.45, a relative risk reduction of 54%, an absolute risk reduction of 1.6% and number needed to treat of 62.

It is very important for the perception of the effect size whether ARR or RRR is used. Take as an example, a study in which 1% of the patients in the placebo group and 0.6% of the patients in the intervention group died. ARR for death is 0.4% (1%-0.6%), whereas RRR for death is as much as 40% (100x(1%-0.6%)/1%). Since RRR is a larger number, RRR is naturally often used in abstracts and marketing material.

The example shows how a moderate absolute reduction resulting in a moderate death rate of 0.4% can be presented as a fairly large relative risk reduction of 40%. Both values are correct and both should be stated instead of just the one. This is because the way of presenting an effect might lead to an erroneous interpretation of a result and should be avoided.

It is important to note that just because an effect in a study is statistically significant this does not mean that it is of a clinically relevant. Consequently, it is not sufficient to state that a statistically significant effect has been found, or state the p-value. The effect size must be stated in relation to its clinical relevance. To ensure the best possible transparency the experimental and control event rates as well as ARR should be stated. The following article offers an example illustrating that the minimum clinically important difference varies in different studies depending on a number of factors: Pain relief that matters to patients: systematic review of empirical studies assessing the minimum clinically important difference in acute pain [10] (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28215182/).

1.10. Evaluation of safety

The safety (including potential risks) of a health technology is equally important to patients as are the probable benefits. Safety is relevant both for pharmaceutical products and for medical devices. Positive as well as negative effects will nearly always be attached to the use of a technology, and the risk scenario should always be examined. You can find more information about ‘Therapeutic window’ in Non-Clinical Development module.

The HTA risk analysis should always include both the patients and the staff or caregivers who are to use the technology. As more and more health technologies are intended for patients' self-management the focus on safety aspects that are important to patients should be thoroughly assessed. Patients can contribute by pointing to the most patient relevant risks and their acceptability for further examinations.

The following safety aspects can provide examples for patients who help formulating safety questions to be included in the HTA assessment:

- Safety requirements for the application of the technology - what are the requirements for marketing authorisation or certification?

- Terminology and definitions - how is “safety” defined when it comes to the technology in question? Do patients, developers and regulators use the same benefit-risk preferences?

- Identification of risks - which adverse effects can be expected? How do patients evaluate or manage these adverse effects?

- The importance of the adverse effects - how frequent and serious are the adverse effects? Are they associated with increased mortality and morbidity?

- Are other safety concerns important for patients evaluated (e.g. safety issues related to alternative interventions)?

- Patient acceptance of adverse effects - how do patients accept the adverse effects? Patients should pay attention to which groups have been asked about tolerance of adverse effects because the tolerance threshold is very low when the technology is used for patients with less serious diseases or conditions.

1.11. Patient involvement in synthesising

The concept of “synthesis” can be defined in different ways. In terms of synthesis in an HTA context the definition 'Synthesis is a combination of often different conceptual comparisons to form a whole (construction of an interpretation)' is the most comprehensive. This means that the parts to be synthesised are different and that it will be necessary to undertake weighing and interpretation.

The synthesis phase is clearly the part of an HTA with the greatest complexity and challenge, despite the fact that it has a central role in the HTA process. One of the reasons may be the particular interface for the HTA appraisal (recommendation) between science and policy, especially if there is a lack of knowledge about how HTA results are actually included in the basis for decisions or a lack of a clear and transparent methodological framework.

Patients can play an important role in synthesising data. Patients can make sure that the weighing of patient relevant elements is high.

For further information on synthesising please see HTA Course 2, HTA Bodies and Principles.

1.12. Patient involvement in appraisals

Appraisals are based on synthesising all data included in the HTA and should be consistent with the HTA framework.

Documenting the arguments for the appraisal, advantages and disadvantages, is important irrespective of the outcome. This will provide the best foundation for patients to keep advocating and justifying either support of the appraisal - or the opposite.

When the appraisal is made publicly available patients or patient groups can:

- Check that their local HTA body has a mechanism to review and to give feedback on recommendations (or ask for one) to ensure recommendation procedures are accountable and fair.

- If a review and feedback mechanism exists, patients and patient groups can review and provide feedback to recommendations to ensure patient evidence and information was considered, consistent with data and information on values provided.

- Communicate summaries of recommendations that can be understood by lay persons.