What is pharmacovigilance (PhV)?

| Site: | EUPATI Open Classroom |

| Course: | Pharmacovigilance - Risk management |

| Book: | What is pharmacovigilance (PhV)? |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 28 June 2025, 11:52 AM |

1. What is pharmacovigilance (PhV)?

(This section is organised in the form of a book, please follow the blue arrows to navigate through the book or by following the navigation panel on the right side of the page.)

The WHO defines PhV as: ‘the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other medicine-related problem.

The EU Commission (EC) in its Commission Staff Working Document[1] defines PhV as: ‘Pharmacovigilance is planned monitoring of the safety of medicines so that anything that affects their safety profile can be swiftly detected, assessed, and understood and appropriate measures can be taken to manage the issue and assure public health.’

Before receiving a marketing authorisation (MA) a medicine’s safety and efficacy has to be assessed and approved by the respective regulatory authority. Data are predominantly based on the results from clinical trials (usually so-called randomised controlled trials (RCT)). Trial participants (patients) are selected according to stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria and followed up very closely under controlled conditions. It follows that a medicine at the time of its authorisation, has been tested in a relatively limited number of selected patients for a defined time period. In sum, not all safety issues can be addressed or reported at the time of authorisation due to the recognized limitations of clinical trials. In contrast, after authorisation, the medicine may be used by a heterogenous population, for a longer time, often with other concurrent diseases and other medicines, under real world conditions. This is when certain, especially rare, adverse reactions (often also called side effects, which is the common lay term)[2] may emerge. Post authorisation however provides the opportunity to learn more about the safety of a medicine.

Therefore, continuous and careful monitoring of the safety profile of all medicines throughout their lifecycle and especially their use in everyday practice is essential in identifying and minimising risk. In the EU each marketing authorisation holder (MAH), national competent authority (NCA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) are under a legal obligation to operate a pharmacovigilance system. The overall EU pharmacovigilance system works through cooperation between the EU Member States, EMA and the European Commission.

[1] Commission Staff Working Document Accompanying the document Commission Report

Pharmacovigilance related activities of Member States and the European

Medicines Agency concerning medicinal products for human use (2012 –2014)

{COM(2016) 498 final}

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=SWD:2016:0284:FIN:EN:PDF

[2] EUPATI will use the term ‘adverse reaction’ instead of ‘side effect’ since this is the proposed term by regulatory authorities

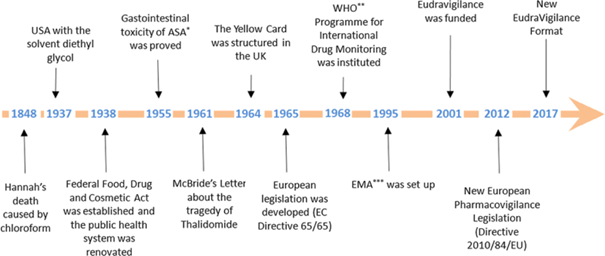

2. How did pharmacovigilance develop?

- One of the earlier reported events was when a young girl, Hannah, died after chloroform anaesthetic before removal of an infected toenail. While the cause of death was not determined at that time, it did begin to raise awareness of adverse events related to anaesthesia. It’s interesting to think about how many centuries went by without this type of detection or oversight.

- US and FDA: 1906, the US Federal Food and Drug Act provided the basic elements for consumer protection. 1911, regulation against false therapeutic drug indications. 1937, there were more than 100 deaths associated with diethylene glycol as a solvent used in a sulfanilamide elixir. Public outcry led to the creation of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Its aim was to renovate the public health system and introduce protections regarding the safety of drugs before their market approval.

- WHO: 1968, the World Health Organisation (WHO) initiated its Programme for International Drug Monitoring in response to the thalidomide disaster detected in 1961 .

- EU and EMA: 1995, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) was created. 2004 Introduction of Risk Management Plans (RMP) and review of EU PhV system. 2010/12 New PhV legislation operational (amending Regulation 726/2004 and Directive 2001/83 and Commission Implementing Regulation (IR) 520/2012) and Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) established, 2017 new enhanced EudraVigilance (EV) system.

All these events (and more) and legislative changes paved the way for increased awareness regarding the conduct of Pharmacovigilance activities to safeguard patient safety throughout the lifecycle of medicines.

While there are many significant historical events that contributed to the genesis of PhV, the exemplary milestones shown in the following graph are just a few of the significant ones:

Figure 1: Timeline of the historical evolution of

Pharmacovigilance.

*ASA:

acetylsalicylic acid; **WHO: World Health Organisation; ***EMA: European

Medicines Agency

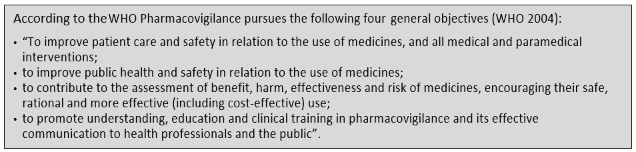

3. EU Pharmacovigilance – objectives - aims - tasks

Following the above definition of pharmacovigilance, according to the EMA the underlying objectives of the applicable EU legislation for pharmacovigilance are:

- preventing harm from adverse reactions in humans arising from the use of authorised medicinal products within or outside the terms of marketing authorisation or from occupational exposure;

- promoting the safe and effective use of medicinal products, in particular through providing timely information about the safety of medicinal products to patients, healthcare professionals and the public.

Specific aims of pharmacovigilance are to:

- Maintain a robust monitoring system for new safety issues.

- Implement effective approaches to minimise risk.

- Install procedures for rapid decision making and triggering actions in case of (immediate) safety concerns

- Improve patient care and safety in relation to the use of medicines and all medical and paramedical (services that support medical work, such as nursing, first aid, radiography) interventions.

- Improve public health and safety in relation to the use of medicines.

- Contribute to the assessment of benefit, risk, and effectiveness (including cost-effectiveness) of medicines.

- Secure the accessibility of information about the safety of medicinal products to patients, healthcare professionals and the public.

- Promote understanding, education and training in pharmacovigilance and its effective communication to the public.

- Monitor impact of measures and activities and ensure continuous improvement of pharmacovigilance system

The above list incorporates what the WHO calls the general objectives.

Pharmacovigilance is therefore an activity

contributing to the protection of patients’ and public health.

Main pharmacovigilance related tasks:

The pharmacovigilance process can be broken down into the following key tasks:

- Assessing the known and potential risks of each medicine before marketing and developing plans to collect data and minimise those risks (risk management planning); (See lesson 2 on risk management)

- Collecting and managing data of possible adverse reactions (ADR); (see section 2 below on ADRs)

- Signal detection and management - analysing the data (reports of suspected adverse reactions) to identify ‘signals’ (any new or changing safety issue); (see section 1.5 on Signals)

- Routine benefit-risk monitoring of medicines via periodic safety update reports (PSURs).

Europe-wide reviews and evaluation of important safety and benefit-risk issues and decision on whether and which (regulatory) action to take; e.g., PhV referrals (in a referral procedure, the EMA is requested to conduct a scientific assessment of the safety concern for the EU).

- Acting to protect public health (including regulatory action).

- Managing information on products under additional monitoring, and products that have been withdrawn.

- Identifying and reducing the risk of medication errors before and after the authorisation of a medicine.

- Assessing and co-ordinating studies after marketing through post-authorisation safety studies and post-authorisation efficacy studies.

- Carrying out inspections to ensure company pharmacovigilance systems comply with good pharmacovigilance practice.

- Communicating in a clear, effective and timely manner about safety-related issues to relevant stakeholders.

- Interacting with and engaging key stakeholders, including patients, healthcare professionals, the pharmaceutical industry, other parts of the regulatory system (including international regulators), academia, the media, and wider civil society

- Monitoring performance of the system and its components, including compliance with legal obligations and standards.

- Continuous development and improvement of systems (including IT infrastructure), guidelines and standards, and promotion of research to address knowledge gaps.

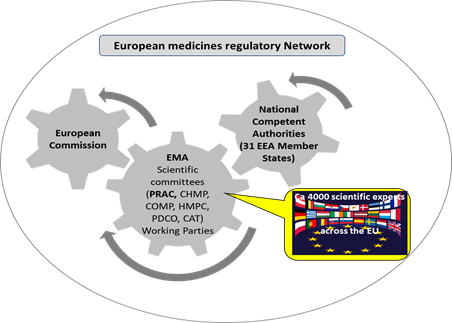

4. Stakeholders in pharmacovigilance

Key stakeholders directly involved in pharmacovigilance activities include:

- Regulatory authorities, including

- the European Commission (EC) is the competent authority for centrally authorised products (CAP) and the legal authority that underpins the EU PhV system andprovides the legislative framework needed to carry out its functions in the most efficient way.

- the European Medicines Agency (EMA): central role in the EU system, co-ordinating its activities and providing technical, regulatory and scientific support to the Member States (MS) and industry.

- the National Competent Authorities (NCAs) (member states regulatory authorities): organise and supervise information collection on and reporting of suspected adverse reactions of medicines, particularly spontaneous reports from patients and health care professionals (HCP) (required by law[1] ); take the lead (rapporteur and co-rapporteur teams) in evaluating and analysing data when a safety issue is assessed at the European level (a PhV referral); etc.

- the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC): an EMA scientific committee in the revised European PhV system (since 2012); members include experts in PhV and regulation working within the NCAs, representatives of patients and HCPs, and scientific experts in areas such as epidemiology, signal detection, biological medicines and risk communication nominated by the EC; responsible for the assessment of safety issues at EU level; also monitors many of the PhV activities. It is at the core of the EU signal management process.

The medicines regulatory authorities in 31 European Economic Area (EEA)

countries, the EMA and the European Commission closely collaborate and work in

partnership as a network (European medicines regulatory network) to

discuss and deal swiftly with any emerging problem in the interest of patients'

access to safe and efficacious medicines.

Figure 2: Simplified schematic of the European medicines regulatory network

- Patients and patient organisations (PO):

- POs work with some NCAs to facilitate adverse reaction reporting; number of POs involved per Member State varies from 1 to 20;

- user-test adverse reaction reporting forms;

- review relevant safety communications (see lesson 4);

- patient representatives are members of PRAC; have input to all activities of the Committee; supply relevant perspectives to all aspects of its work

- broader consultations may form part of PhV referrals

- patient representatives participate in

scientific advisory groups (SAGs), (expert groups convened to supply

specialist input)

- Health care professionals (HCP) (Doctors, pharmacists, nurses and all other professionals working with medicines):

- are members of PRAC; participate in all activities of the Committee; supply relevant perspectives to all aspects of its work;

- broader consultations may form part of PhV referrals;

- review relevant safety

communications

- the Pharmaceutical industry: individual marketing authorisation holders (MAHs) have specific responsibilities under the legislation in terms of running a system of PhV, monitoring and reporting for their products. MAHs are responsible for collecting, reviewing and analysing information on suspected adverse reactions received via patients, healthcare professionals, scientific literature, clinical trials and studies or other sources. They have to report this information to regulatory authorities for further evaluation on an expedited basis (via sharing suspected adverse reaction reports as well as any urgent safety issues identified) and on a periodic basis (via Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSURs)). MAHs communicate and collaborate with regulators as appropriate in dealing with PhV issues.

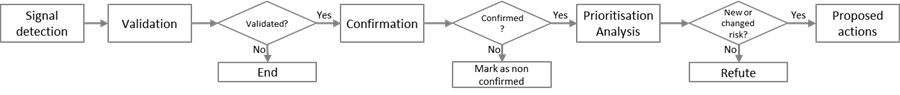

5. The PhV process in short

The entire PhV process—from systems that monitor for and detect possible adverse effects (safety signals) through to regulatory action to mitigate risks—is coordinated across the regulatory network, the pharmaceutical industry and health systems. The PhV system receives a wide range of input including that from non-EU regulators, academia, health professionals and patients and via several other channels.

A signal is defined as “information arising from one or multiple sources, including observations and experiments, which suggest a new potentially causal association, or a new aspect of a known association between an intervention and an event or set of related events, either adverse or beneficial, that is judged to be of sufficient likelihood to justify verificatory action.”

(Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No. 520/2012 of 19 June 2012 on the performance of pharmacovigilance activities provided for in Regulation (EC) No. 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Directive 2001/83/ EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. EUROPEAN COMMISSION https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2012/520/oj

Signal management in the EU focuses on adverse outcomes and involves a set of activities performed to determine whether there are new risks associated with an active substance or a medicinal product or whether risks have changed.

(Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP): module IX: signal management (Rev 1). EUROPEAN MEDICINES AGENCY <https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-gvp-module-ix-sig-nal-management-rev-1_en.pdf> (2017).)

A safety signal therefore is information on a new or known adverse event that is potentially caused by a medicine and that warrants further investigation.

(COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT (2017) https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017SC0201&from=EN)

In the following a brief outline of the PhV process is given including the concepts, the steps followed and the actors involved when dealing with a suspected adverse reaction of a medicine (how to come from an adverse event to an adverse reaction (ADR) (see below).

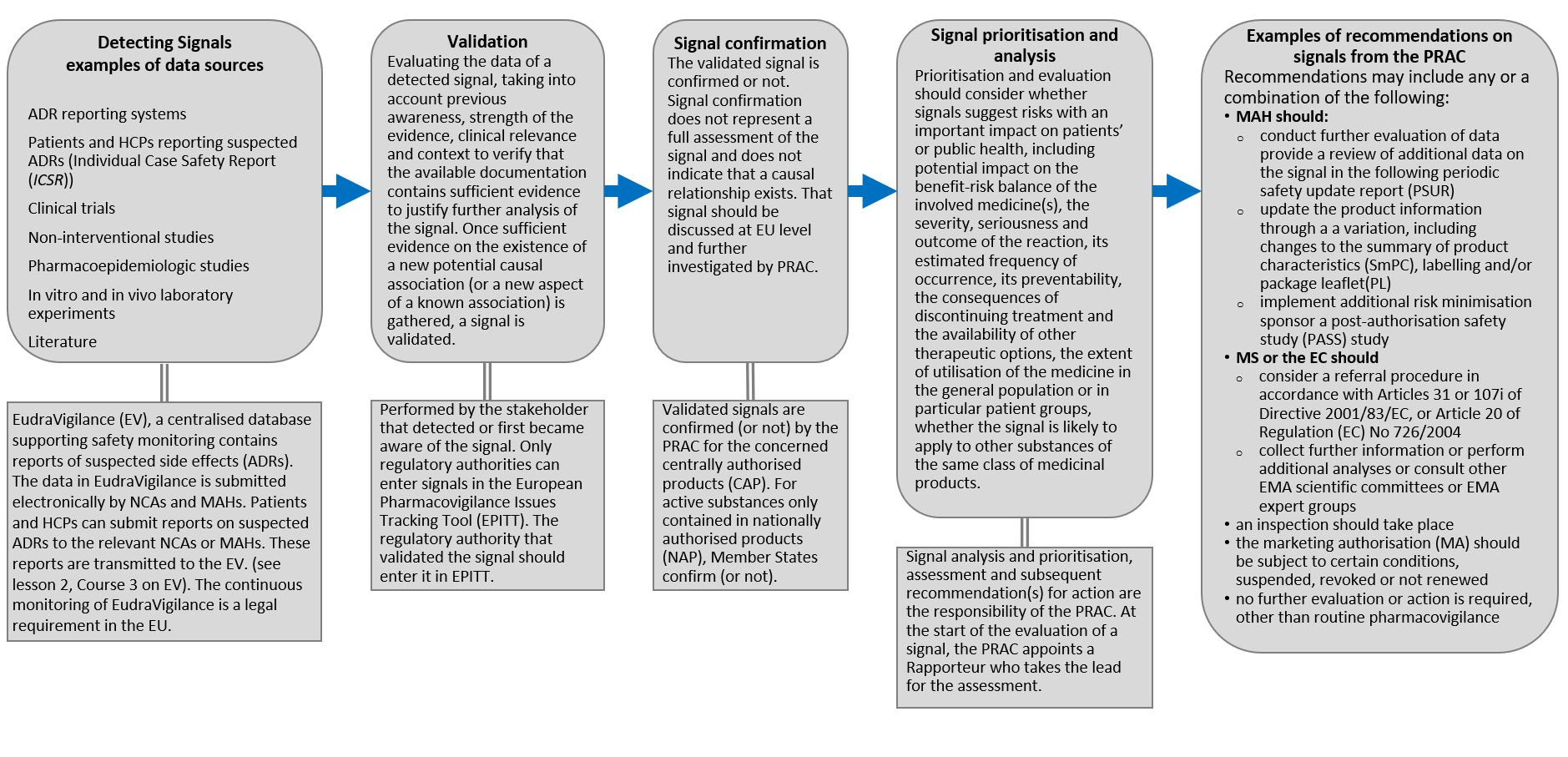

The process starts with the PhV system receiving information from which a signal for a suspected adverse reaction of a medicine is identified (signal detection, performed by the EMA, Member States and MAHs). For centrally authorised medicinal products (CAPs), the EMA is responsible for EudraVigilance data monitoring in collaboration with PRAC, and Member States, in collaboration with the EMA for medicinal products authorised nationally (NAPs). Figure 3 shows the process steps together with explanatory notes in a high-level schematic.

Figure.3: High-level workflow schematic of the pharmacovigilance signal management process. Adapted from: HMA Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP)Module IX – Signal management (Rev 1) (2017) available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-gvp-module-ix-signal-management-rev-1_en.pdf

Figure.4: High-level workflow schematic of the pharmacovigilance signal management process. Adapted from: HMA Guideline on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP)Module IX – Signal management (Rev 1) (2017) available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-gvp-module-ix-signal-management-rev-1_en.pdf

The following gives a short overview of the steps in the signal management process.

Detecting Signals examples of data sources: ADR reporting systems, Patients and HCPs reporting suspected ADRs (Individual Case Safety Report (ICSR)), Clinical trials, Non-interventional studies, Pharmacoepidemiologic studies, In vitro and in vivo laboratory experiments, Literature etc.

Signal data are transmitted and held in the EudraVigilance (EV), a centralised database supporting safety monitoring that contains reports of suspected adverse reactions (ADRs). The data in EudraVigilance is submitted electronically by NCAs and MAHs. Patients and HCPs can submit reports on suspected ADRs to the relevant NCAs or MAHs. The continuous monitoring of EudraVigilance is a legal requirement in the EU (see lesson 2 on EV).

Validation: Evaluating the data of a detected signal, taking into account previous awareness, strength of the evidence, clinical relevance and context to verify that the available documentation contains sufficient evidence to justify further analysis of the signal. Once sufficient evidence on the existence of a new potential causal association (or a new aspect of a known association) is gathered, a signal is validated. Performed by the stakeholder that detected or first became aware of the signal. Only regulatory authorities can enter signals in the European Pharmacovigilance Issues Tracking Tool (EPITT). The regulatory authority that validated the signal should enter it in EPITT.

Signal confirmation: The validated signal is confirmed or not. Signal confirmation does not represent a full assessment of the signal and does not indicate that a causal relationship exists. That signal should be discussed at EU level and further investigated by PRAC. Validated signals are confirmed (or not) by the PRAC for the concerned centrally authorised product (CAP). For active substances only contained in nationally authorised products (NAP), Member States confirm (or not).

Signal prioritisation and analysis: should consider

- whether signals suggest risks with an important impact on patients’ or public health, including potential impact on the benefit-risk balance of the involved medicine(s),

- the severity, seriousness and outcome of the reaction, its estimated frequency of occurrence, its preventability, the consequences of discontinuing treatment and the availability of other therapeutic options,

- the extent of utilisation of the medicine in the general population or in particular patient groups,

- whether the signal is likely to apply to other substances of the same class of medicinal products.

Signal analysis and prioritisation, assessment and subsequent recommendation(s) for action are the responsibility of the PRAC. At the start of the evaluation of a signal, the PRAC appoints a Rapporteur who takes the lead for the assessment.

Examples of recommendations on signals from the PRAC: Recommendations may include any or a combination of the following:

- MAH should:

- conduct further evaluation of data and provide a review of additional data on the signal in the following periodic safety update report (PSUR

- update the product information through a variation, including changes to the summary of product characteristics (SmPC), labelling and/or package leaflet (PL)

- implement additional risk minimisation measures

- sponsor a post-authorisation safety study (PASS) study

- MS or the EC should

- an inspection should take place

- the marketing authorisation (MA) should be subject to certain conditions, suspended, revoked or not renewed

-

no further evaluation or action is required, other than routine pharmacovigilance

Adapted from

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/questions-answers-article-31-pharmacovigilance-referral-procedures_en.pdf

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/questions-answers-urgent-union-procedures-article-107i-directive-2001/83/ec_en.pdf

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-gvp-module-ix-signal-management-rev-1_en.pdf

6. Summary - Safety monitoring of medicines

The European regulatory system for medicines monitors the safety of all medicines that are available on the European market throughout their life cycle. EMA has a committee dedicated to the safety of medicines for human use—the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee, or PRAC. If there is a safety issue with a medicine that is authorised in more than one Member State, the same regulatory action is taken across the EU and patients and healthcare professionals in all Member States are provided with the same guidance. All suspected adverse reactions that are reported by patients and healthcare professionals or become known by other sources (e.g. from clinical trials) must be entered through NCAs or MAHs into EudraVigilance, the EU web-based information system operated by EMA for managing and analysing information on suspected adverse reactions to medicines which have been authorised or being studied in clinical trials in the European Economic Area (EEA). This electronic reporting is obligatory for marketing authorisation holders and sponsors of clinical trials. These data are continuously monitored by EMA, the Member States regulatory authorities (NCAs) and marketing authorization holders (MAHs) in order to identify any possible new safety information (safety signal) (obligatory monitoring according to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 520/2012 (article 18)). EMA provides online public access to reports of suspected adverse reactions for authorised medicines in EudraVigilance, the European database of suspected drug-reaction reports. The PRAC has a broad remit covering all aspects of pharmacovigilance. In addition to its role in risk assessment, the committee provides advice and recommendations to the European medicines regulatory network on risk management planning and benefit-risk assessment for medicines after marketing. In addition, the EU’s pharmacovigilance legislation enables the PRAC to hold public hearings during safety reviews of medicines if deemed useful. Public hearings are intended to support the committee’s decision-making by providing perspectives, knowledge and insights into the way medicines are used in clinical practice. A comprehensive overview of the pharmacovigilance legislation, which came into effect in 2012, and which introduced a range of tasks and streamlined existing responsibilities for regulators and the pharmaceutical industry in the European Union (EU) can be found here: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/pharmacovigilance/legal-framework/implementation-pharmacovigilance-legislation .