5.1. Types of Observational Studies: Cohort Studies

| Site: | EUPATI Open Classroom |

| Course: | Epidemiology and Pharmacoepidemiology |

| Book: | 5.1. Types of Observational Studies: Cohort Studies |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Friday, 11 July 2025, 4:55 AM |

Description

1. Cohort studies

(This section is organised in the form of a book, please follow the blue arrows to navigate through the book or by following the navigation panel on the right side of the page.)

A cohort is any group of individuals sharing a common characteristic. For instance, this may be:

- Demographic factor such as age, race, or sex or born within a given time frame;

- Constitutional factor such as blood group or immune status;

- Behaviour or activity such as smoking or having been at a certain public event; or

- Circumstance such as living near a toxic waste site

Cohort studies are longitudinal, observational studies, which investigate predictive risk factors and health outcomes within one or more cohorts. Cohort studies may comprise healthy persons, or may start by sampling people with a disease or condition. They differ from clinical trials, in that no intervention, treatment, or exposure (see below) is administered to the participants. Because of the observational nature of cohort studies, they predominantly serve to determine association (correlation) between an exposure and outcome (e.g., disease) rather than a causal relationship.

Exposures can be general characteristics, such as age or sex; risk factors, such as smoking or alcohol consumption; a health-related intervention; or a disease. Exposure can be categorised as present or absent or by levels of exposure, such as blood pressures.

A central feature of a cohort study is that for a cohort of all exposed persons, the risk (or the rate) for the outcome can be calculated as [(persons with both exposure and outcome) / (all exposed persons)]. If a comparison group of unexposed persons is included, a relative risk can be calculated.

Of note, a comparison group is not a defining feature of a cohort study: for example, when the aim of the cohort study is the description of the disease course or the prognosis.

Cohort studies may be prospective or retrospective.

A prospective cohort study is also called a concurrent cohort study, where the participants are followed up for a period of time (often years) and the outcomes of interest are recorded. The studies are designed before any information is collected. The outcome of interest should be common; otherwise, the number of outcomes observed will be too small to be statistically meaningful (indistinguishable from those that may have arisen by chance). All efforts should be made to avoid sources of bias such as the loss of individuals to follow up during the study. Prospective studies usually have fewer potential sources of bias and confounding than retrospective studies.

In a retrospective cohort study both the exposure and outcome have already occurred at the outset of the study. Retrospective studies therefore look backwards, e.g., examine exposures to a possible risk in relation to an observed outcome. Often, information is used that has been collected for reasons other than research, such as administrative data or medical records. While this type of cohort study is less time consuming and costly than a prospective cohort study, it is more susceptible to the effects of confounding and bias, and special care should be taken to avoid this. However, if the outcome of interest is uncommon, the size of a prospective investigation required to estimate relative risk is often too large to be feasible and retrospective studies are an alternative. In retrospective studies the odds ratio [1] provides an estimate of relative risk.

Example: Selection Bias in a Retrospective Cohort Study

In a retrospective cohort study, selection bias occurs if selection of exposed & non-exposed subjects is somehow related to the outcome.

- Investigating occupational exposure (an organic solvent) occurring 15-20 years ago in a factory.

- Exposed & unexposed subjects are enrolled based on employment records, but some records were lost.

- Suppose there was a greater likelihood of retaining records of those who were exposed and got disease. Indeed, 20% of employee health records were lost or discarded, except in “solvent” workers who reported illness (1% loss)

- Workers in the exposed group were more likely to be included if they had the outcome of interest.

Source: Challenges of Observational and Retrospective Studies, Kyoungmi Kim, Ph.D,March 8, 2017

[1] An odds ratio (OR) is a measure of association between an exposure and an outcome. The OR represents the odds that an outcome will occur given a particular exposure, compared to the odds of the outcome occurring in the absence of that exposure. It is the ratio of the probability a thing will happen over the probability it won’t. In numerical terms, an OR above 1 reflects an increased probability and an OR below 1 a decreased probability of the outcome of interest to happen.

1.1. Prospective cohort studies

Prospective cohort studies (PCS) observe one or more groups of participants longitudinally over time (often years) to determine the incidence of a specific outcome or various outcomes after an exposure or several exposures (for instance medicines, interventions or risk factors).

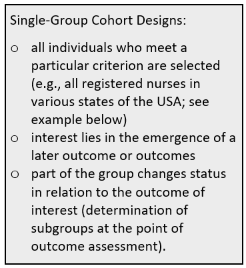

In principle prospective cohort studies are characterised in the following way: A cohort of participants is drawn from source population (the sample should be representative of that population). Participants should be free of the outcome(s) of interest but otherwise have common characteristics and the potential to develop that outcome. Baseline information is collected from all participants, notably their exposure status, using exactly the same data collection methods for all. Cohort groups may be selected on the basis of exposures at baseline, e.g., smokers vs. non-smokers. The first group then is the ‘exposure’ group, the second group is free of the exposure. The participants in the two groups are then followed "longitudinally," i.e., over a period of time, usually for years, and assessed at intervals to determine if and when they develop the outcome(s) of interest (e.g., disease) and whether their exposure status changes. The non-exposed group serves as the comparison group (‘control’) providing an estimate of the baseline or expected amount of the outcome or disease occurrence in the community. Comparison groups can be defined at the beginning or created later using data from the study (e.g., age group, amount of a specific food group consumed). In single-group cohort studies (see box) those participants who do not develop the outcome of interest are used as internal controls. The incidence of the outcome in the exposed group is compared with the incidence of the outcome in the non-exposed group (risk or relative risk). If the incidence is substantially different in the exposed group compared to the non-exposed group, the exposure is likely to be associated with the outcome. Investigators can eventually use the analysis to answer various questions, e.g., about the associations between "risk factors" and disease outcomes. For example, one could identify smokers and non-smokers at baseline and compare their subsequent incidence of developing heart disease. Alternatively, one could group subjects based on their body mass index (BMI) and compare their risk of developing heart disease or cancer.

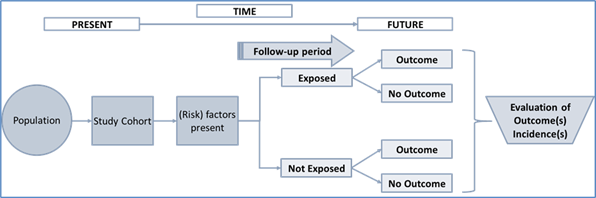

The following figure shows a schematic of the principal setup of a prospective cohort study.

Figure 1: Principal setup of a prospective cohort study with two participant groups.

1.2. Prospective cohort studies: Points to consider

Advantages

- the only observational study design that directly investigates risk of disease and the factors contributing to it

- allows examination of multiple outcomes of a single exposure

- good for rare or unusual types of exposures, e.g., contact with a chemical spill in a factory, unusual occupational exposures (e.g., asbestos, or solvents in chemical manufacturing)

- best for common outcomes

- ethically safe

- advantage over retrospective cohort and case control studies because baseline exposure status is correctly assessed, not only recalled

- clarity of temporal sequence (Did the exposure precede the outcome?): since at the time of entry into the cohort study, when their exposure status is established, individuals do not have the outcome, more clearly indicates the temporal sequence between exposure and outcome, gives some indication of causality

- accurate measurement of exposure variable, other variables, and outcomes: may help in reducing the bias in measurement of exposure

- can measure the change in exposure and outcome over time

- yield true incidence rates and relative risks

- may uncover unanticipated associations with outcome

- avoid selection bias at enrolment: reduces the possibility that the results will be biased by selecting subjects for the comparison group who may be more or less likely to have the outcome of interest, because the outcome is not known at baseline when exposure status is established.

Drawbacks

- data analysis needs sufficient follow-up time after study start, therefore not appropriate for rare outcomes/diseases or those that take a long time to develop (long latency)

- can be costly and time consuming

- not appropriate for studying multiple exposures[1]

- confounding factors within the sample groups may be difficult to identify and control for, thus influencing the results, e.g. non-random allocation of exposure: possibility that the association found may be explained by other variables that differ between exposed and non-exposed participants and that also have an association with the outcome studied. If these other variables were measured, they can be adjusted for in the analysis, but frequently these factors are unmeasured, measured imprecisely, or even unknown

- participants moving between exposure/non-exposure categories or not properly complying with methodology requirements

- if a significant number of participants are not followed up (lost, death, dropped out) this may impact the validity of the study and may decrease the study’s power, and introduce so called attrition bias – a significant difference between the groups of those that did not complete the study

Key Concept: The distinguishing feature of a prospective cohort study is that at the time that the investigators begin enrolling participants and collecting baseline exposure information, none of the participants has developed any of the outcomes of interest, and eventually, an association between exposure and subsequent outcome can be established.

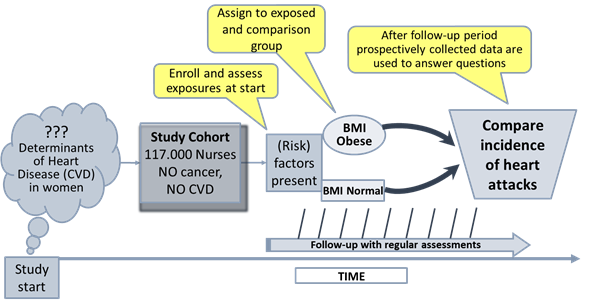

Example: The Nurses’ Health Study, the Nurses’ Health Study II and the Nurses’ Health Study III are well-known cohort studies established in 1976, 1989, and 2010 respectively, that have followed over 100,000 nurses. Participants are sent detailed questionnaires every two years. The nurses report information on their diet, lifestyle, medicines, family history, work arrangements, family life, etc. They also report on any diseases that they develop. The studies revealed many correlations between environmental factors and risks for health conditions in diverse topics and has resulted in hundreds of scientific papers and extensive press coverage[2].

This exemplary study is shown in the following figure (Fig. 3). To note: the graph illustrates one of the subgroups from this large single group study addressing a question in a specific area. Participants with the hypothesised risk factor are assigned to one group (exposed), the comparison group is comprised of participants without this risk factor but otherwise similar (internal control).

Figure 2: Schematic of a subgroup from the Nurses’ Health Study

addressing a specific question.

(BMI: Body Mass Index; 18,5-24,9 normal weight; 30-39,9 obese; CVD:

Cardiovascular Disease). Adapted from: https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/mph-modules/ep/ep713_analyticoverview/EP713_AnalyticOverview3.html

[1] However looking at different exposures in the same cohort would be possible as you could split the cohort based on different exposures (e.g. one analysis looking at the impact of BMI, another analysis of the same cohort looking at smoking, a third analysis looking at living in rural vs non-rural areas, etc.). This will increase the complexity and risks that the cohort subgroups become relatively small. You may also increase confounding.

[2] Nurses‘ Health Study https://www.nurseshealthstudy.org/

1.3. Retrospective cohort studies

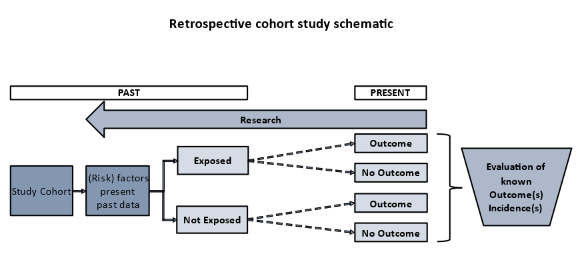

The methodology in retrospective cohort studies is similar to that in prospective cohort studies. However, in contrast to prospective studies, retrospective studies are conceived after both, the exposure and the outcomes, have already occurred. The exposures are determined before looking at the existing outcome data to see whether exposure to a (risk) factor is associated with a statistically significant difference in the outcome incidences. Cohorts are defined first according to whether or not the outcome was observed and second, going back in time, by identifying a cohort of individuals at a point in time before they had developed the outcome(s) of interest. Further, in order to classify individuals as "exposed" or "unexposed", investigators try to establish their exposure status at that point in time. For this, information or data, obtained in the past, often for other purposes, is collected from existing sources (e.g., health or employment records, data from previous, prospective studies). The cohort is then “followed up” retrospectively to determine whether and how many individuals subsequently developed the outcome(s) of interest.

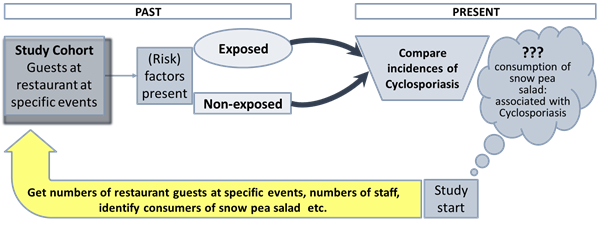

The following figure shows a schematic of the principal setup of a retrospective cohort study.

Figure 3: Principal setup of a retrospective cohort study.

1.4. Retrospective cohort studies: Points to consider

Advantages

- useful for tracking the progress of a disease with a long latency period from study start

- can address the effects of exposures that no longer occur (e.g., discontinued medical treatments)

- are less time consuming and costly than prospective cohort studies, the actual period of interest may cover many years but the time to complete the retrospective study is only as long as it takes to collate and analyse the data

- can examine multiple effects of a single exposure, or yield information on multiple exposures

- particularly efficient for the study of rare exposures, especially occupational and “natural history” exposures

- no ethical issues in terms of collecting data if legally accessible

- not useful for the study of emerging, new exposures

- rely on existing records or subject recall which may be less accurate and complete than data collected prospectively (e.g., no records exist for the hypothesis of interest, records were not designed for the study)

- are more susceptible to the effects of bias: for example, the exposure may have occurred some years previously and adequate reliable data on exposure may be unavailable or incomplete; information on confounding variables may be unavailable, inadequate or difficult to collect

- prevent the investigator from reducing confounding and bias because collected information is restricted to data that already exists

- information on other risk factors may be inaccurate

- difficulty to identify an appropriate exposed cohort and an appropriate comparison group

- differential loss to follow up can introduce bias

- selection bias can occur since the outcomes are already known at the time of selection

Key Concept: The distinguishing feature of a retrospective cohort study is that the investigators conceive the study and begin identifying and allocating participants after exposures and outcomes have already occurred.

Example: A retrospective cohort study was used to determine the source of cyclosporiasis,

a parasitic disease that caused an outbreak among members of a residential

facility in Pennsylvania in 2004[1].

The investigation indicated that consumption of snow peas was implicated as the

vehicle of the cyclosporiasis outbreak.

A simplified schematic of this

example is shown in the following figure (Fig. 4). To note: The study was not

pre-planned. Investigator had to go back to past data that was not necessarily

acquired in a precise, predetermined way. Follow up may have been incomplete.

For interest:

It is also possible to find cohorts to study based on archived information. One

investigator used archives from a Florentine dowry investment fund to study

mortality among women who lived in Florence, Italy from 1425-1545, centuries

before the study was conducted[2].

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of Cyclosporiasis associated with snow peas—Pennsylvania, 2004. MMWR 2004;53:876–8. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5337a6.htm

[2] Morrison AS, Kirshner J, Molho

A. Life cycle events in 15th century Florence: records of the Monte delle doti.

Am J Epidemiol. 1977 Dec;106(6):487-92. doi:

10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112496. PMID: 337798. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/337798/