3. Key GxPs in Medicine

| Site: | EUPATI Open Classroom |

| Course: | Introduction to Regulatory Affairs |

| Book: | 3. Key GxPs in Medicine |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 3 July 2025, 5:38 AM |

1. Key GxPs in Medicine

(This section is organised in the form of a book, please follow the blue arrows to navigate through the book or by following the navigation panel on the right side of the page.)

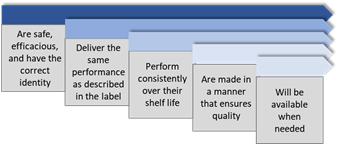

Patients expect medicines to be safe, effective, of high quality and accessible.

GxP rules and guidelines ensure that all aspects of the medicines development process are conducted according to the best methods for safety, efficacy , and quality.

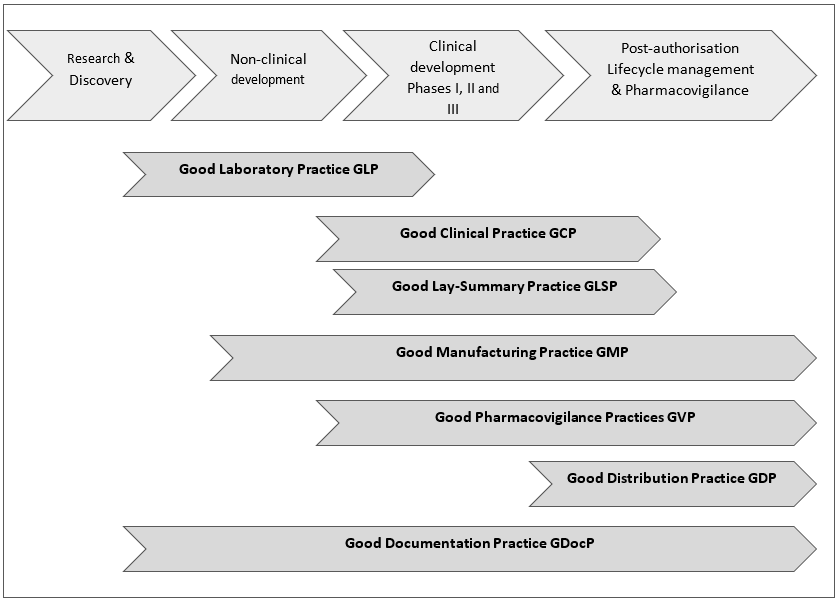

The most relevant GxPs in the pharmaceutical industry are:

- Good Laboratory Practice (GLP)

- Good Clinical Practice (GCP)

- Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)

- Good Pharmacovigilance Practice(GVP)

- Good Distribution Practice (GDP)

- Good Documentation Practice (GDocP)

The extent of what GxPs are included in a GxP system often depends on the respective jurisdiction, but GLP, GCP and GMP are always comprised as a minimum. Further, in the legislation some GxPs are subsumed under another GxP, e.g. Good documentation practice (GDP) can be found under Good manufacturing practice (GMP).

Figure 1 below is a high-level overview of Key GxPs along the medicines R&D process. Of note: the Good Lay Summary Practice GLSP is included here among the Key GxPs because it is of particular interest for patients/patient advocates.

Figure 1: High-level overview of Key GxPs along the medicines R&D process

2. Good Laboratory Practice (GLP)

As early as a research project has led to a development candidate this compound will be carefully investigated in the non-clinical development phase. These activities are covered by GLP, which was devised to promote the development of quality test data, both to help protect human health and the environment and to allow reliable scientific data to be shared between countries.

The current definition of GLP (cGLP), incorporated in the EU legislation and also in that of numerous countries worldwide, is given by the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Developmen (OECD) document ‘Principles of Good laboratory practice’: “Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) is a quality system concerned with the organizational process and the conditions under which non-clinical health and environmental safety studies are planned, performed, monitored, recorded, archived and reported”. It should be applied unless specifically exempted by national legislation.

GLP covers safety testing not only in medicines, but also in other areas like pesticides, cosmetics, or veterinary drugs. Of course, the scope here is restricted to medicines, i.e. to “ ... the non-clinical safety testing of test items contained in medicinal products ... required by regulations for the purpose of registering or licensing ...The purpose of testing these test items is to obtain data on their properties and/or their safety with respect to human health and/or the environment.” (OECD Principles of GLP). Medicines could be synthesized chemicals, naturally occurring substances, biologics or living organisms.

As far as medicines development is concerned, the GLP Principles, in their regulatory sense, apply only to studies which are:

- non-clinical, i.e. mostly studies on animals or in vitro, including their analytical aspects;

- designed to obtain data on the properties and/or the safety of items with respect to human health and/or the environment;

- intended to be submitted to a national regulatory authority with the purpose of registering or licensing the tested substance or any product derived from or containing it.

Depending on national legislation, the GLP requirements for non-clinical laboratory studies conducted to evaluate drug/medicine safety cover the following classes of studies:

- Single dose toxicity

- Repeated dose toxicity (sub-acute and chronic)

- Reproductive toxicity (fertility, embryo-foetal toxicity and teratogenicity, peri-/postnatal toxicity)

- Mutagenic potential

- Carcinogenic potential

- Toxicokinetics (pharmacokinetic studies providing systemic exposure data for the above studies)

- Pharmacodynamic studies designed to test the potential for adverse effects (Safety pharmacology)

- Local tolerance studies, including phototoxicity, irritation and sensitisation studies, or testing for suspected addictive and/or withdrawal effects.

GLP is intended to guarantee that all laboratory results are reliable before going to the next step, i.e. ‘First-in-Human’ trials. As safety testing also takes place along clinical trials GLP is therefore relevant in clinical development for the respective functions.

The test facility must meet strict standards in terms of procedures, equipment, and personnel. And every study must be planned, performed, monitored, recorded, archived, and reported under the proper conditions.

A few points to remember:

GLP Principles are independent of the site where studies are performed. They apply to studies planned and conducted in a manufacturer’s laboratory, at a contract or subcontract facility, or in a university or public sector laboratory.

GLP is not directly concerned with the scientific design of studies. The scientific value is judged by the respective regulatory authority evaluating a MAA. However, adherence to GLP will add to the overall credibility of the data.

Through the application of approved Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) many sources of systematic error and artefacts may be avoided.

The requirement to formulate a study plan with a defined scientific purpose for the study will diminish the incidence of incomplete or inconclusive data.

When implementing GLP in a test facility, it is important to clearly differentiate between the formal, regulatory use of the term Good Laboratory Practice and the general application of “good practices” in scientific investigations. Any laboratory may consider that it is following good practices in its daily work. This does not comprise GLP compliance with all the requirements of the OECD GLP Principles.

For more details, please look at the respective EMA website: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/compliance/good-laboratory-practice-compliance

Legal

basis:

Directive 2004/10/EC on the harmonisation of laws,

regulations and administrative provisions relating to the application of the

principles of good laboratory practice and the verification of their

applications for tests on chemical substances. (incorporates: OECD Series on principles

of Good laboratory practice and compliance monitoring, Number 1, OECD Principles on Good Laboratory

Practice (as

revised in 1997))

Directive 2004/9/EC on the inspection and verification of good laboratory practice (GLP)

2.1. Good Clinical Practice GCP

GCP is an international ethical and scientific quality standard defined by the ICH for the design, oversight, recording and reporting trials for the products that involve testing in humans. The standard outlines the requirements of a clinical trial and the roles and responsibilities of the involved people and their function. It ensures that no human experiments are performed just for the sake of medical advancement.

Compliance with this standard laid out by the ICH and other guidelines should achieve:

- Protection of participants in clinical trials. Ensure that rights, safety and well-being of trial participants are protected, consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

- Confidentiality of records that could identify participants. Respecting privacy and confidentiality rules in accordance with the applicable legislative requirement(s)

- Quality and integrity of the data collected. Ensure that the clinical trial data are credible.

The principles of the ICH GCP guideline as the core document are listed below:

- Before a clinical trial is initiated, the possible risks must be considered against the expected benefits. The trial must only go ahead if the expected benefits outweigh the foreseeable risks.

- The trial must be based on sound scientific knowledge and its procedures must have been approved by the relevant regulatory authority and must have obtained a positive opinion by a review board or ethics committee before the trial proceeds.

- A trial should be conducted in compliance with a clear, detailed protocol

- All personnel involved in conducting a trial should have the proper education, training, and experience to perform his or her role.

- All trial participants must have given consent freely and based on full information about what they're consenting to.

- Any medical care provided must be given by a qualified medical professional.

- All data should be recorded, handled, and stored in a way that allows it to be accurately reported, interpreted, and verified, irrespective of the type of media used.

- Any records in which trial participants could be identified should be kept confidential.

- Investigational products should be adequate to support the proposed clinical trial based on available non-clinical and clinical information and should be manufactured, handled, and stored in accordance with applicable good manufacturing practice (GMP). They should be used in accordance with the approved protocol.

These principles are further elaborated and cover topics such as the roles and responsibilities of the Institutional Review Board / Independent Ethics Committee (IRB/IEC), the investigator, the sponsor; resources, trial protocol, trial management and compliance with protocol, data handling and record keeping, safety reporting, informed consent and medical care of trial participants, quality management, manufacturing, packaging, labelling, and coding investigational product(s), monitoring, auditions, the investigator’s brochure (a compilation of the clinical and nonclinical data on the investigational product(s) that are relevant to the study of the product(s) in humans. Its purpose is to provide the investigators and others involved in the trial with the information to facilitate their understanding of the rationale for, and their compliance with many key features of the protocol)

Legal basis:

Directive 2005/28/EC), the 'GCP Directive'

ICH E6 (R2) ‘Guideline for Good clinical practice’; adopted by the EU in 1996, which provides a unified standard for the ICH regions (European Union, Japan, the United States, Canada, and Switzerland) to facilitate the mutual acceptance of data from clinical trials by the regulatory authorities in these jurisdictions.

Directive 2001/20/EC, the 'Clinical Trial Directive'

When the Regulation (see below) becomes applicable on 31 January 2022, it will repeal the Clinical Trials Directive (EC) No. 2001/20/EC and national legislation that was put in place to implement the Directive

Regulation (EU) No 536/2014, the 'Clinical Trial Regulation’; becomes applicable on 31 January 2022

Specific Guidelines have been developed for ATMPs (October 2019).

Guidelines on Good Clinical Practice (GCP) specific for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMP)

For more details in view of the EMA on GCP see:

https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/compliance/good-clinical-practice

For more information on clinical trial authorisation, safety monitoring, GCP inspections, and GCP and GMP requirements for clinical trials in the European Economic Area (EEA), see EudraLex - Volume 10 - Clinical trials guidelines.

2.2. Good Manufacturing Practice GMP

1. Manufacturing / Import Authorisation (MIA)

Any company located in the European Economic Area (EEA) that intends to produce or import human medicines, needs an authorisation issued by the respective regulatory authority. A manufacturing / import authorisation (MIA) will only be issued when the company can show it complies with GMP (e.g., follows the EU GMP guidelines) and passes regular inspections. Importers are also responsible to ensure that the third country manufacturer they are importing from complies with GMP.

Of Note: "Import" refers to goods coming from third countries into the EU and not to movement of goods between Member States. Movement within the EU on the other hand, is subject only to the holding of a Wholesale Distribution Authorisation.

2. GMP overview

GMP sets out best practice methods and standards for manufacturers to ensure their products are of consistent high quality, appropriate for their intended use, are safe and comply with the marketing authorisation or clinical trial authorisation, are packaged and labelled correctly, are uncontaminated and contain the ingredients and have the strength they claim to have. This applies to all medicines intended for the EU market and to all manufacturing sites no matter where in the world they are located. Legislation in the EU to control and guarantee that these requirements are observed is detailed and continuously adapted to new scientific, technical and system developments. In fact, GMP can be considered one key element of what the EU guidelines call quality management, which, along with quality control and quality risk management, forms part of an overall pharmaceutical quality system. (see also section 3 Quality system)

It should be noted that GMP standards are not prescriptive or “cookbook” instructions on how to manufacture products. They are a series of performance-based requirements that must be met during manufacturing. There may be many ways, a company can fulfil GMP requirements. It is the company's responsibility to determine the most effective and efficient quality process that meets both, business and regulatory needs.

Practically all legislation and guidelines concerning GMP in numerous countries across the world follow a series of basic principles which are listed in a high-level outline in the following. For more information the relevant detailed legislative documents and guidelines should be consulted.

The guidelines concern all aspects of production, requiring, for example, that:

- Manufacturing facilities are of adequate size and kept in good condition with clean and hygienic manufacturing areas and access restricted to authorised personnel only

- Manufacturing facilities maintain controlled environments in order to prevent cross-contamination that may render the product unsafe for human use.

- Manufacturing processes are clearly defined and controlled. All critical processes are validated to ensure consistency and compliance with specifications.

- Equipment is properly calibrated and maintained in order to consistently produce reliable results

- Any changes to the manufacturing process are evaluated and changes that affect the quality of the product are validated as necessary.

- Instructions and procedures are clear and unambiguous

- Employees have the appropriate qualifications and training

- Processes are reliable and consistent; this needs to be properly documented and archived following Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), manufacturing instructions, analytical methods, etc.

- The correct materials, containers and labels are used; they need to comply with their specifications and be correctly identified. Their use must be recorded and traceable.

- Quantity and quality of the product are within defined limits and any deviations investigated and documented.

- Records of manufacture (including distribution) that enable the complete history of a batch to be traced are retained in a comprehensible and accessible form.

- A system is in place for recalling any batch from sale or supply.

- Complaints about marketed products are examined, the causes of quality defects are investigated, and appropriate measures are taken with respect to defective products and to prevent recurrence.

Legal basis:

Regulation No. 1252/2014 and Directive 2003/94/EC, applying to active substances and medicines for human use;

Directive 2001/83/EC (Title IV Manufacture and Import)

Directive 2001/20/EC (Article 13 Manufacture and import of investigational medicinal products)

Eudralex Volume 4 of "The rules governing medicinal products in the European Union" contains the EU GMP guidelines which provide interpretation of these principles and guidelines, supplemented by a series of annexes that modify or augment the detailed guidelines for certain types of product, or provide more specific guidance on a particular topic.

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2017/1569 supplementing Regulation (EU) 536/2014 by specifying principles and guidelines for GMP for investigational medicinal products for human use and arrangements for inspections (applicable as from the date of entry into application of Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 on Clinical Trials)

Commission Directive (EU) 2017/1572 supplementing Directive 2001/83/EC as regards the principles and guidelines of GMP for medicinal products for human use (applicable as from the date of entry into application of Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 on Clinical Trials)

Specific GMP Guidelines have been developed for ATMPs

Guidelines on Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP)

2.3. Good Pharmacovigilance Practices GVP

Pharmacovigilance has been defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other medicine-related problem.

Good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) are a set of measures designed to facilitate the performance of pharmacovigilance in the EU. GVP apply to marketing-authorisation holders, the EMA and medicines regulatory authorities in EU Member States. They cover medicines authorised centrally via the EMA as well as medicines authorised at national level.

In line with the general definition, underlying objectives of the applicable EU legislation for pharmacovigilance are:

- preventing harm from adverse reactions in humans arising from the use of authorised medicinal products within or outside the terms of marketing authorisation or from occupational exposure; and

- promoting the safe and effective use of medicinal products, in particular through providing timely information about the safety of medicinal products to patients, healthcare professionals and the public.

Pharmacovigilance is therefore an activity contributing to the protection of patients’ and public health.

1. GVP and the European Union Pharmacovigilance System

The EU pharmacovigilance system arguably may be considered one of the most advanced and comprehensive systems in the world. The EU-GVP serves as a robust and transparent instrument that regulates and clarifies the processes of monitoring the safety of medicines on the European market, prevention, detection and assessment of adverse reactions (including medication errors and overdose). Such approach guarantees a high level of patient and public health protection throughout the EU.

The key elements of the EU Pharmacovigilance system as addressed in GVP:

- (EU)-Qualified Person for PV (QPPV) and the respective back-up procedures;

- Organisation of the pharmacovigilance system (the pharmacovigilance system master file (PSMF), a detailed description of the pharmacovigilance system used by the MAH with respect to one or more authorised medicine);

- Periodic safety update report;

- Databases, listing of the data bases used for pharmacovigilance services, registration with the EudraVigilance system and description of processes used for electronic reporting;

- Contractual arrangements with other contracted persons, organisations or service providers involved in the fulfilment of pharmacovigilance obligations;

- Training, records of regular education/training of staff involved in pharmacovigilance activities;

- Documentation, locations of different types of pharmacovigilance source documents, including archiving arrangements;

- Quality Management System;

- Inspections and Audits.

2. Guideline on GVP

In the past the European Commission published pharmacovigilance guidance for human medicinal products (Volume 9A). The most recent of this guidance documents dates from September 2008. With the application of the new pharmacovigilance legislation as from July 2012 Volume 9A is replaced by the good pharmacovigilance practice (GVP) guideline released by the European Medicines Agency. The guideline covers medicines authorised centrally via the EMA as well as medicines authorised at national level. The guideline on GVP is divided into chapters that fall into two categories:

- modules covering major pharmacovigilance processes;

- product- or population-specific considerations.

Such division allows independent update of the separate modules, assures that the system remains flexible, dynamic and sensitive to the changing requirements of the constantly developing health system. Any member of the EU regulatory network as well as any other stakeholder, including members of the public, and non-regulatory stakeholder organisations, can contribute their proposals for corrections, revision and/or addition of GVP Modules. Since their first version and adoption several Modules have being extensively revised and amended.

Modules covering major pharmacovigilance processes

GVP modules I to XVI cover major pharmacovigilance processes. The module numbers XI, XII, XIII and XIV stay void, as their planned topics have been addressed by other guidance documents on the EMA's website. Annexes provide additional required information: definitions, templates, other guidelines. (including policy on access to EudraVigilance data), and also ICH topics and guidance.

Product- or population-specific considerations

The chapters on product- or population-specific considerations are available for vaccines, biological medicinal products and the paediatric population.

The following Table 2 provides an overview of the GVP Guideline and the adopted GVP modules therein.

Table 2. An overview of the adopted GVP modules

|

GVP adopted Modules |

First published or |

|

Guidelines on good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP) |

2021 |

|

GVP Module I: Pharmacovigilance systems and their quality systems |

2012 |

|

GVP Module II: Pharmacovigilance system master file (Rev. 2) |

2017 |

|

GVP: Module III: Pharmacovigilance inspections |

2014 |

|

GVP Module IV: Pharmacovigilance audits (Rev. 1) |

2015 |

|

GVP Module V: Risk management systems (Rev. 2) |

2017 |

|

GVP Module VI: Collection, management and submission of reports of suspected adverse reactions to medicinal products (Rev. 2) |

2017 |

|

GVP Module VI (Addendum I): Duplicate management of suspected adverse reaction reports |

2017 |

|

GVP Module VII: Periodic safety update report |

2013 |

|

GVP Module VIII: Post-authorisation safety studies (Rev. 3) |

2017 |

|

GVP Module VIII Addendum I: Requirements and recommendations for the submission of information on non-interventional post-authorisation safety studies (Rev. 3 new text first published) |

2020 |

|

GVP Module IX: Signal management (Rev. 1) |

2017 |

|

GVP Module IX: Addendum I: Methodological aspects of signal detection from spontaneous reports of suspected adverse reactions |

GVP Module X: |

|

GVP Module X: Additional monitoring |

2013 |

|

GVP Module XV: Safety communication (Rev. 1) |

2017 |

|

GVP Module XVI: Risk minimisation measures: selection of tools and effectiveness indicators (Rev. 2) |

2017 |

|

GVP Module XVI: Addendum I: Educational materials |

2015 |

For more information on Pharmacovigilance and Risk management processes and procedures Course 3: Pharmacovigilance - Risk management should be consulted.

Legal basis:

Directive 2001/83/EC as amended (with respect to nationally authorised medicines)

Regulation (EC) No. 726/2004 as amended (with respect to centrally authorised medicines)

The GVP Guideline

https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/post-authorisation/pharmacovigilance/good-pharmacovigilance-practices

2.4. Good Distribution Practice GDP

The quality and the integrity of medicinal products can be affected by a lack of adequate control of the wholesale distribution of medicinal products and active substances. Good distribution practice (GDP) describes the minimum standards that a wholesale distributor must meet to ensure that the quality and integrity of medicines is maintained throughout the supply chain.

Compliance with GDP ensures that:

- medicines in the supply chain are authorised in accordance with European Union (EU) legislation

- medicines are stored in the right conditions at all times, including during transportation

- contamination by or of other products is avoided

- an adequate turnover of stored medicines takes place

- the right products reach the right addressee within a satisfactory time period

The distributor should also put in place a tracing system to enable finding faulty products and an effective recall procedure.

GDP also applies to the sourcing, storage and transportation of active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) and other ingredients used in the production of the medicines.

Text from EMA: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/post-authorisation/compliance/good-distribution-practice

Legal basis:

European Commission guidelines:

Commission guideline 2013/C 343/01 on Good Distribution Practice of medicinal products for human use based on Article 84 and Article 85b(3) of Directive 2001/83/EC

Commission guideline 2015/C 95/01 on principles of Good Distribution Practice for active substances for medicinal products for human use based on Article 47 (4) of Directive 2001/83/EC

Link to Questions and Answers document

2.5. Good Documentation Practices GDocP

Good Documentation Practices (GDocP) are an essential of GxP compliance. Good documentation constitutes an important part of the pharmaceutical quality system and is key to operating according to GMP requirements. GDocP should be implemented to define, document, and log every critical action in the development, manufacture, and distribution of a medicine or medical device. It should assure data integrity as a key requirement of GxP, through the accuracy, completeness, consistency and reliability of the records and data throughout the data life cycle. These principles require that documentation is attributable, legible, contemporaneously recorded, original and accurate (referred to as ALCOA). This is expanded to ‘ALCOA-plus’ (or ALCOA+) by adding that documentation should be complete, consistent, enduring and available. These characteristics apply equally to both, paper and electronic records.

In essence, ALCOA defines the fundamentals for ensuring data integrity and critical elements of Good Documentation Practice as shown in the following detailed description of the ALCOA+ principles taken from the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-Operation Scheme (PIC/S) Guidance ‘Good Practices for Data Management and Integrity in Regulated GmP/GdP Environments’, PI 041-1, (July 2021), Section 7.5: Basic data integrity principles applicable to both paper and electronic systems:

ALCOA(+) principles

A number of attributes are considered of universal importance to data. These include that the data are:

Attributable

It should be possible to identify the individual or computerised system that performed a recorded task and when the task was performed. This also applies to any changes made to records, such as corrections, deletions, and changes where it is important to know who made a change, when, and why.

Legible

All records should be legible – the information should be readable and unambiguous in order for it to be understandable and of use. This applies to all information that would be required to be considered Complete, including all original records or entries. Where the ‘dynamic’ nature of electronic data (the ability to search, query, trend, etc.) is important to the content and meaning of the record, the ability to interact with the data using a suitable application is important to the ‘availability’ of the record.

Contemporaneous

The evidence of actions, events or decisions should be recorded as they take place. This documentation should serve as an accurate attestation of what was done, or what was decided and why, i.e., what influenced the decision at that time.

Original

The original record can be described as the first-capture of information, whether recorded on paper (static) or electronically (usually dynamic, depending on the complexity of the system). Information that is originally captured in a dynamic state should remain available in that state.

Accurate

Records need to be a truthful representation of facts to be accurate. Ensuring records are accurate is achieved through many elements of a robust Pharmaceutical Quality System. This can be comprised of:

- equipment related factors such as qualification, calibration, maintenance and computer validation.

- policies and procedures to control actions and behaviours, including data review procedures to verify adherence to procedural requirements

- deviation management including root cause analysis, impact assessments and CAPA

- trained and qualified personnel who understand the importance of following established procedures and documenting their actions and decisions.

Together, these elements aim to ensure the accuracy of information, including scientific data that is used to make critical decisions about the quality of products.

Complete

All information that would be critical to recreating an event is important when trying to understand the event. It is important that information is not lost or deleted. The level of detail required for an information set to be considered complete would depend on the criticality of the information. A complete record of data generated electronically includes relevant metadata (see section 9).

Consistent

Information should be created, processed, and stored in a logical manner that has a defined consistency. This includes policies or procedures that help control or standardize data (e.g. chronological sequencing, date formats, units of measurement, approaches to rounding, significant digits, etc.).

Enduring

Records should be kept in a manner such that they exist for the entire period during which they might be needed. This means they need to remain intact and accessible as an indelible/durable record throughout the record retention period.

Available

Records should be available for review at any time during the required retention period, accessible in a readable format to all applicable personnel who are responsible for their review whether for routine release decisions, investigations, trending, annual reports, audits or inspections.

If these elements are appropriately applied to all applicable areas of GMP and GDP related activities, along with other supporting elements of a Pharmaceutical Quality System, the reliability of the information used to make critical decisions regarding medicinal products should be adequately assured.

ALCOA is also the system used by WHO, EMA, FDA, and others and incorporated in guidelines (see below).

While some GDocP standards are codified by authorities, others are not but are considered as part of cGMP (with emphasis on the "c", or "current"). Some authorities release or adopt guidelines. While not law, (regulatory) authorities will inspect against these guidelines in addition to the legal requirements. The application of GDocP is also expanding to the cosmetic industry, excipient and ingredient manufacturers.

The EC details documentation requirements in the context of GMP in the guideline ‘EudraLex - Volume 4 - GMP - Chapter 4: Documentation’ which contains the following items:

- Required GMP Documentation,

- Generation and Control of Documentation,

- Good Documentation Practices,

- Retention of Documents,

- Specifications,

- Manufacturing Formula and Processing Instructions,

- Procedures and records

Legal basis:

Directive 2001/83/EC Article 47f

Guideline examples:

European Commission guideline ‘EudraLex - Volume 4 - GMP - Chapter 4: Documentation’ which contains the following items

WHO Technical Report Series No. 996, 2016. Available at: WHO_TRS_996_annex05.pdf (rx-360.org)

EMA draft Guideline on computerised systems and electronic data in clinical trials (June 2021)

FDA Guidance for Industry Data Integrity and Compliance with Drug CGMP Questions and Answers (2018)

Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-Operation Scheme (PIC/S) guidance PI 041-1 (July 2021).

Chapter 7 cf. of that guideline specifically concerns the Good document management practices (GdocPs) that can be summarised by ALCOA+.