1. Pharmacoepidemiology

| Site: | EUPATI Open Classroom |

| Course: | Epidemiology and Pharmacoepidemiology |

| Book: | 1. Pharmacoepidemiology |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 3 June 2025, 3:05 AM |

Description

1. Pharmacoepidemiology

(This section is organised in the form of a book, please follow the blue arrows to navigate through the book or by following the navigation panel on the right side of the page.)

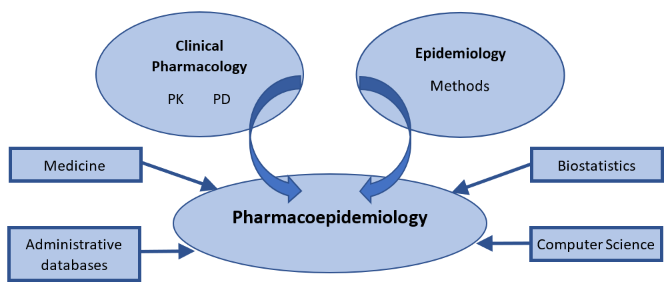

For medicines it provides an estimate of the probability of beneficial and adverse effects in a population. It can be called a bridge science spanning both clinical pharmacology and epidemiology. Pharmacoepidemiology concentrates on clinical patient outcomes from therapeutic interventions by using methods of epidemiology and applying them to understand the determinants of beneficial and adverse effects, effects of genetic variation on medicine effect, duration-response relationships, clinical effects of medicine-drug interactions, and the effects of medication non-adherence. Pharmacoepidemiology also involves the conduct and evaluation of public programmes to improve medication use on a population basis.

Although the main contributions to pharmacoepidemiology come from epidemiology and clinical pharmacology, other disciplines, like medicine, biostatistics, computer science and administrative databases inform pharmacoepidemiology as well.

Figure 1.: Illustration

of the relationship between pharmacoepidemiology and several contributing disciplines.

PK: pharmacokinetics; PD: pharmacodynamics.

Pharmacovigilance (or postmarketing surveillance) (see Epidemiology/pharmacoepidemiology

an integral part of Pharmacovigilance) is

an important part of pharmacoepidemiology that involves continuous monitoring

in a population for unwanted effects and other safety concerns arising in medicines

that are already on the market. In addition, without pharmacovigilance, there would

be limited information about the effectiveness of medicines in practice such as

how a medicinal product is used, whether people continue to take it, and what

outcomes are associated with it in diverse patient populations. Remember that

efficacy refers to whether the medicinal product can produce a specific

therapeutic outcome in a controlled environment. This is investigated in

clinical trials. In the “real world,” effectiveness needs to be considered. In

other words, can the medicinal product produce the desired therapeutic outcome

in practice where the environment is not controlled and is it sufficiently safe?

You can read more about efficacy and effectiveness in Health

Technology Assessment module, in the course HTA

and Evaluation Methos: Quantitative.

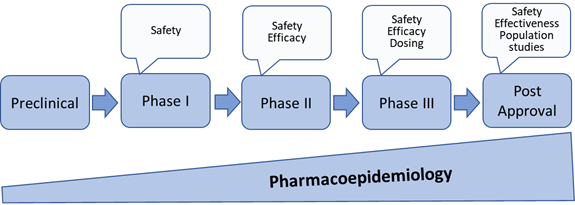

Since pharmacoepidemiology studies provide information about medicines utilisation and safety, these studies are important throughout the entire medicines’ life cycle. Therefore, Pharmacoepidemiology starts from discovery research and continues through pre-marketing research and into post-approval monitoring and safety studies (Figure 2). This applies as well to vaccines and medical devices.

Figure 2: Pharmacoepidemiology through medicines development and post approval[1]

[1] Upadhyay Srishti *, Shrivastava Saumya, Kumar Deepak, Kabra Atul, Baghel Uttam Singh, Pharmacoepidemiology: A Review, Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Development.2019; 7(2):83-87 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22270/ajprd.v7i2.464

1.1. Possible goals of pre- or post-approval epidemiology programmes

- Monitor use and effects of medicines in populations.

- Measure occurrence of underlying disease.

- Study natural history of underlying disease.

- Medicine utilisation and prescription monitoring.

- Patient characterisation.

- Therapeutic intervention and disease associations: risks and benefits, intended and unintended effects.

- Evaluation of risk minimisation measures.

1.2. Applications and contributions of pharmacoepidemiology

Some examples of applications and contributions of pharmacoepidemiology are:

- Prediction of the magnitude (frequency and size) of the likely effects of the medicine, both intended and unintended.

- Development of measurement scales to capture patient-reported outcomes (PRO) that are linked to efficacy and safety measures.

- Design of clinical efficacy trials.

- Development of an expected safety profile.

- Development of risk management plans and post-marketing safety studies.

- Reassurance about medicines safety

Supplementing the information available from premarketing studies – better quantitation of the incidence of known adverse and beneficial effects, e.g.,

- in patients not studied prior to marketing (e.g., the elderly, pregnant women);

- as modified by other medicines and other illnesses;

- relative to other medicines used for the same indication

- New types of information not available from premarketing studies

- discovery of previously undetected adverse and beneficial effects (e.g., uncommon, delayed, or rare effects)

- formulation of therapeutic guidelines

- finding material for possible new indications

- understanding how the medicine is being utilised in routine clinical practice

- describe the characteristics of patients who receive the medicine

- patterns of medicines prescribing (the appropriateness of use)

- medication adherence and persistence patterns,

- identification of predictors for medication use.

- evaluation of effects of medicines overdose in everyday use

- determine the frequency and distribution of medicines use outcomes in a population (“Real-world data” (RWD) and “Real-world evidence” (RWE), focussing on

- what is being used (assessment of specific medicines being used in certain situations)

- how it is being used (assessment of the patterns of use, including how much, where and when, and by whom);

- why it is being used (assessment of the reasons for medicines-taking behaviours and the functions that medicines serve in society)

- Facilitate pharmaco-economic evaluation

- Inform interventions or public health policy decisions that may need to be developed

1.3. Examples of pharmacoepidemiology studies that address practice-based research questions

- Is there a relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and the metabolic syndrome? The investigators reviewed 70 abstracts and articles of case reports, retrospective database studies, retrospective clinical trials, and pharmacoepidemiology studies to find the answer to this question.[1]

- Is the use of antidepressants associated with the risk of hip/femur fractures? A case-control study was conducted using a Dutch database to address this question.[2]

- Do medications used to treat diabetes decrease or increase the risk of cardiovascular disease? A retrospective cohort study of diabetes patients using The Health Information Network database was conducted. [3]

- Have medication adherence trends for cardiovascular medications improved over time? Investigators used a retrospective cohort study of Medicare beneficiaries who were discharged from the hospital after their first myocardial infarction to address this question.[4]

- How are atypical antipsychotics being used in children? A retrospective analysis of state Medicaid claims data was used.[5]

[1] Kabinoff GS, Toalson PA, Healy KM, McGuire HC, Hay DP. Metabolic issues with atypical antipsychotics in primary care: Dispelling the myths. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;5:6-14.

[2] van den Brand MWM, Samson MM, Pouwels S, et al. Use of anti-depressants and the risk of facture of the hip or femur.

Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1705-1713.

[3] Margolis DJ,Hofstad MA, Strom BL.Association between serious ischemic cardiac outcomes and medications used to treat diabetes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(8):753-759.

[4] Choudhry NK, Setoguchi S, Levin R, Winkelmayer WC, Shrank WH. Trends in adherence to secondary prevention medications in elderly post-myocardial infarction patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(12):1189-1196.

[5] Pathak P, West DS, Martin BC, Helms M, Henderson C. Evidence-based use of second-generation antipsychotics in a state Medicaid pediatric population, 2001-2005. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(2):123-129.