Why measure Health-Related Quality of Life?

| Site: | EUPATI Open Classroom |

| Course: | HTA and Evaluation Methods: Qualitative |

| Book: | Why measure Health-Related Quality of Life? |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 3 June 2025, 3:13 AM |

1. Why measure Health-Related Quality of Life?

(This section is organised in the form of a book, please follow the blue arrows to navigate through the book or by following the navigation panel on the right side of the page.)

There are many reasons why we might want to measure HRQoL:

- Patients and healthcare providers as well as payers are interested in the added value a technology (health intervention or use of health technology) has to offer. HRQoL can serve as a common measure of gains from any technology as perceived by patients. Patient groups can use these measures to compare the values of new technologies.

- HRQoL measures are also often used in relation to the costs of new health technologies in an economic evaluation to support decision-making in HTA processes.

- HRQoL measures provide useful information to care providers as they can be used to screen and monitor patients for psychosocial problems or when auditing healthcare practice.

- HRQoL measures can be used in population surveys of perceived health problems or other aspects of health-services or evaluation research.

- Regulators can use HRQoL measures to support their assessments of new technologies. In fact, in some instances HRQoL changes are accepted as primary or secondary endpoints in clinical trials if justified and explicitly detailed in trial protocols.

For policy makers, who are supposed to decide how to allocate resources in healthcare, and HTA bodies, being able to appraise the value that a new technology may bring compared to other technologies across various types of patients is useful and may support their assessments or decisions. Payers are interested in science-based decisions and quantifying the gains that a treatment can provide for a patient. A generic instrument to measure HRQoL allows a numeric HRQoL score to be calculated but such instruments require qualitative research to design and develop them.

What is a Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY)?

Policy makers and HTA organisations may use a numeric HRQoL score for instance in the calculation of a Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) – although there are ongoing debates about how to use QALYs in healthcare decision making or whether or not to use them at all.

The quality-adjusted life year (QALY) is a generic measure of disease burden, including both the quality and the length of life lived while also taking into account any changes in the health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The QALY therefore is a measure of the value of health outcomes (utility value, see below box) to the people who experience them and is an attempt to combine two different attributes associated with treatment - length of life and quality of life - into a single score/number (an index) that can be compared across different types of treatments (interventions).

One QALY equates to one year in perfect health (the utility value set to 1 (or 100%)). One year of less than perfect health has a quality of life (or utility value) between 0 – 1 (a percentage (in decimals) between 0 and 1). Death has a utility value of 0 (a respondent could choose to record a score below zero – worse than death – where, for instance, they are experiencing severe distress and/or possibly a terminal illness, although many people with terminal illnesses do not have utilities <0).

|

Health Utility Measures Health utility measures are values (or utility weights) associated with a given state of health by the years lived in that state or preferences that patients attach to their health state. Utility values are generic HRQoL measures (HRQoL weights), which are determined either directly, through in-person interviews using measures such as standard gamble, time tradeoff, or willingness to pay, or indirectly through HRQoL instruments. The direct measures involve comparisons against an external metric that a person would be willing to trade to improve their current health state, such as the risk of death (standard gamble), years of life (time tradeoff), or amount of money (willingness to pay). Indirect methods of determining the weight associated with a particular health state use standard descriptive systems such as the EuroQol five dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D) (categorises health states according to five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities (e.g. work, study, homework or leisure activities), pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). An algorithm is then used to compute a utility score integrating both individual and community perspectives. |

1.1. Uses of QALYs

Examples of QUALY use are given below and should be read in conjunction with section 3 “Why measure Health-Related Quality of Life?”. This is not a comprehensive list but highlights some of the more common applications of QUALYs as an instrument. Take special note of the last bullet point, indicating an area where QUALYs are applied by an HTA body (example NICE for more detailed information [1])

QALYs can be used to

- quantify the effectiveness of a new treatment (e.g., new medication) compared to the current treatment for a particular condition.

- to compare the health benefit of a new treatment for one condition with the health benefit of a new treatment for a different condition. For instance, the QALY permits comparison of a new cancer therapy with the health effect of a new Parkinson's medication.

- to inform health insurance coverage determinations, treatment decisions, to evaluate programmes, and to set priorities for future programmes

- to combine data on medical costs with QALYs in

cost-utility analysis to estimate the cost-per-QALY associated with a health

care intervention. This parameter can be used to develop a cost-effectiveness

analysis of any treatment and can be used to allocate healthcare resources,

often using a threshold approach. (in the United Kingdom, the National

Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which advises on the use of

health technologies within the National Health Service, has used "£ per

QALY" to evaluate their utility).

Indeed, the QALY is commonly used in health economic evaluations as a means of quantifying the health effect of a medical intervention or a prevention programme and ultimately to help payers allocate healthcare resources.

[1] QALYs and their role in the NICE decision-making process, Joy Ogden https://wchh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/psb.1562

1.2. Calculation of QALYs

QALYs can be calculated using the following formula which assumes a utility value designated by a score (quality of life) between 1 = perfect health and 0 = dead:

Years of Life x Utility Value = Number of QALYs

This will yield:

- If a person lives in perfect health for one

year, that person will have 1 QALY.

(1 Year of Life × 1 Utility Value = 1 QALY) - If a person lives in perfect health but only for

half a year, that person will have 0.5 QALYs.

(0.5 Years of Life x 1 Utility Value = 0.5 QALYs) -

Conversely, if a person lives for 1 year in a

situation with 0.5 utility (half of perfect health), that person will also have

0.5 QALYs.

(1 Year of Life x 0.5 Utility Value = 0.5 QALYs)

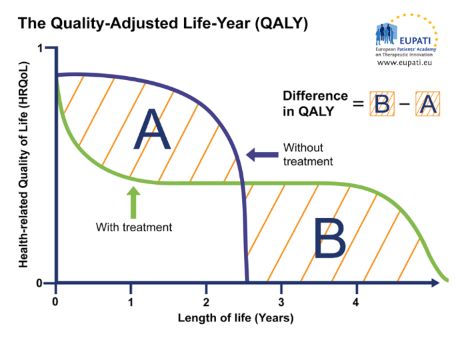

QALY calculations can be used to visualise the relationship between the quality and quantity of life experienced with and without the therapy in question, as in the graph below.

Figure 1: The Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY)

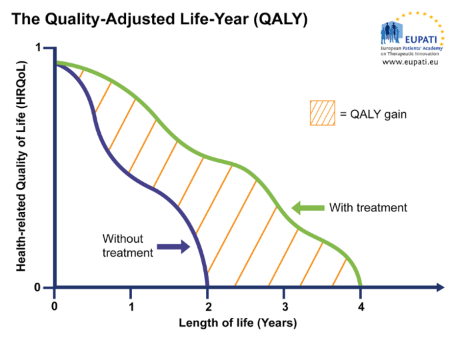

Similar graphs can be used to plot changes in HRQoL over time with and without treatment, providing a visualisation of the QALY gain or loss, respectively. In the graph below, for instance, the treatment provides an increase in HRQoL as well as an extension of life, resulting in a net QALY gain.

Figure 2: The Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY)

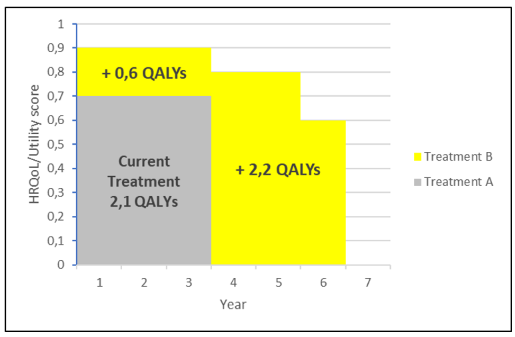

The following graph summarises the essentials of a QUALY calculation for a fictive comparison of two treatments.

Figure 3: a QUALY calculation for a fictive comparison of

two treatments.

-> If a person lives for 3 years

with a disease and the current treatment (treatment A) for that disease with a

utility score of 0.7, that person will have 2.1 QALYs.

(3 Years of Life x 0.7 Utility

Value = 2.1 QALYs)

--> If that person receives a new

treatment (treatment B) whereby his/her utility score increases to 0.9, that

person will now have 2.7 QALYS during the initial 3 years, i.e., the benefit of

the new treatment will add 0.6 QALYs as this is the increase over the current treatment.

(3 Years of Life x 0.2

Additional Utility Value = 0.6 additional QALYs)

---->Thus the overall gain attributable to the new treatment will be 0.6 + 2.2 = 2.8 QALYs

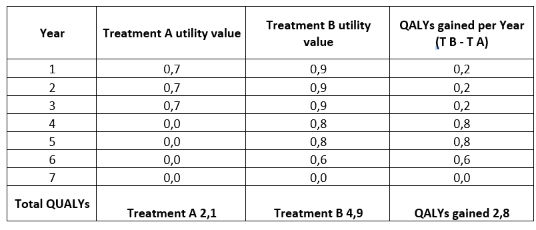

Table 2: Illustration of the scores used in the above graph

1.3. Limitations of QALY – critical debate

Although the QALY is a recognised metric used to evaluate new and innovative health technologies and optimise resource allocation via rational and explicit methodologies, especially in performing cost effectiveness analyses, a number of limitations in its application currently exist and are subject of ongoing critical debate.

Discussion centres around three major themes. These are:

a) Ethical considerations

b) Methodological Issues and Theoretical Assumptions

c) Context or Disease Specific Considerations

For each of these a few issues raised in the debate are briefly illustrated in the following.

- valuing an individual’s life over another’s:

perfect health is difficult, if not impossible, to define, and, further, a perfect state of health does not necessarily make a life more or less valuable - for example, one cannot assume that someone who is in a wheel-chair cannot live as content as someone who isn’t and subsequently be less entitled to care - reducing freedom of choice:

QALYs used to justify overly restricted healthcare budgets, being more prescriptive in what healthcare options are available, system ultimately reduces autonomous patient decisions

- overly utilitarian:

all QALYs are considered equal regardless of individual of situational circumstances. Ranking interventions on grounds of their cost per QALY gained ratio implies a quasi-utilitarian calculus to determine who will or will not receive treatment. - equity issues:

no account for e.g. the overall distribution of health states – particularly since younger, healthier people have many times more QALYs than older or sicker individuals. As a result, QALY analysis may undervalue treatments which benefit the elderly or others with a lower life expectancy.

QALY-based system could exacerbate racial disparities in medicine because there is no consideration of genetic background, demographics, or comorbidities that may be elevated in minority racial groups that do not have as much weight in the consideration of the average year of perfect health.

- measurement techniques:

- measuring utility values with different methodologies can produce different results.

- Study participants often misunderstand utility scales.

- Dissimilar populations may evaluate conditions differently.

- Utility scores do not account for contextual factors such as severity of initial health state, prevalence of disease, parent or caregiver status, or if a population is marginalised.

- Definition of adequate measurements, their validity and the ability to reliably replicate them.

- QALY is the product of utility and time, and time is a non-zero variable. However, in QALY models, utility is assigned an arbitrary scale from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health) and this use of 0 prevents arithmetic operations such as division and multiplication. A potential solution to this would be measuring time and utility using similar units of measurement, which would translate into more meaningful and accurate outcomes.

- employment of league table comparisons of QALYs for different interventions (comparing heterogeneous populations and time periods):

Theoretically, a QALY calculated for angina treatment in 1997 in the UK may well have different results compared to a QALY calculation for angina in Germany in 2005.

- discrimination against new and innovative treatments:

the QALY model requires utility independent, risk neutral constant cost effectiveness and therefore issues a fixed cost for an intervention that does not factor in a potential reduction in costs as technology advances and interventions are refined, such as those falling within the remit of regenerative medicine, which are often expensive initially but significantly reduce in cost over time. Because of these theoretical assumptions, the meaning and usefulness of the QALY is debated.

- limit research on treatments for rare disorders:

upfront costs of the treatments tend to be higher. Officials in the United Kingdom were forced to create the Cancer Drugs Fund to pay for new drugs regardless of their QALY rating because innovation had stalled since NICE was founded.

The European Consortium in Healthcare Outcomes and Cost-Benefit Research (ECHOUTCOME) ran a major study on QALYs as used in HTA. They concluded that "preferences expressed by the respondents were not consistent with the QALY theoretical assumptions" that quality of life can be measured in consistent intervals, that life-years and quality of life are independent of each other, that people are neutral about risk, and that willingness to gain or lose life-years is constant over time.[1] . ECHOUTCOME also released "European Guidelines for Cost-Effectiveness Assessments of Health Technologies," which recommended not using QALYs in healthcare decision making.[2] . Instead, the guidelines recommended that cost-effectiveness analyses focus on "costs per relevant clinical outcome." Instead, the guidelines recommended that cost-effectiveness analyses focus on "costs per relevant clinical outcome."

QALYs have limited value where quality of life is a major consideration but survival is not, thus limiting the utility of the QALY in evaluating the effects of many chronic but not fatal diseases.

In general, younger, healthier groups of people will have many times more QALYs than groups of older, more infirm individuals therefore QALY calculations may undervalue treatments which benefit the elderly or other groups with a lower life expectancy.

[1] Beresniak, Ariel; Medina-Lara, Antonieta; Auray, Jean Paul; De Wever, Alain; Praet, Jean-Claude; Tarricone, Rosanna; Torbica, Aleksandra; Dupont, Danielle; Lamure, Michel; Duru, Gerard (2015). "Validation of the Underlying Assumptions of the Quality-Adjusted Life-Years Outcome: Results from the ECHOUTCOME European Project". PharmacoEconomics. 33 (1): 61–69. doi:10.1007/s40273-014-0216-0. ISSN 1170-7690. PMID 25230587

[2] European Consortium in Healthcare Outcomes and Cost-Benefit Research (ECHOUTCOME). "European Guidelines for Cost-Effectiveness Assessments of Health Technologies" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-08-14