2. Ethical issues

| Site: | EUPATI Open Classroom |

| Course: | HTA and Evaluation Methods: Quantitative |

| Book: | 2. Ethical issues |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 5 July 2025, 8:21 PM |

1. Ethical issues

(This section is organised in the form of a book, please follow the blue arrows to navigate through the book or by following the navigation panel on the right side of the page.)

Ethical issues arising from health technologies have become more prominent over the last several decades. This is due to a combination of factors including:

- Increasingly complex systems for delivering increasingly complex care

- A reappraisal of the assumption that all new health technology is good

- Recognition of the difficult choices that must be made in allocating resources for health

In the field of HTA, ethical issues arise in particular in relation to the following areas:

- Use of technology

- Conduct of research

- Allocating resources

1.1. Use of technology

HTA’s purpose is ’...to inform decision-making in order to promote an

equitable, efficient, and high-quality health system’ (INAHTA definition 2020).

Assessing a technology can provide important information about the balance

between beneficence (doing good) and non-maleficence (doing no

harm). In the end, individual practitioners and patients will ultimately decide

whether a technology will be used or not in a particular case.

***

Short recap of Beneficence and Non-maleficence

Research should be worthwhile and provide value that outweighs any risk or harm. Researchers should aim to maximise the benefit of the research and minimise potential risk of harm to participants and researchers. All potential risk and harm should be mitigated by robust precautions.

The need for a favourable risk/benefit assessment requires an assessment of the probabilities of both the harms and of the benefits that may arise. The term ‘risk’ is generally used for harms but the probability of benefits also needs to be considered. Many kinds of possible harms and benefits need to be taken into account. There are, for example, risks of psychological harm, physical harm, legal harm, societal harm and economic harm and the corresponding benefits. While the most likely types of harms to research participants are those of psychological or physical pain or injury, there may be others costs of a societal nature to consider.

Discovering what will in fact provide a benefit may require exposing

persons to some risk. Conducting research without any risk of causing harm

would prevent many improvements in human welfare. Where the participant may

benefit directly through the research, such risks are more justifiable.

However, where the research project will not benefit the participants directly,

the wider benefits to others in terms of the potential to alleviate disease or

other harms in the future may justify research with some risk but only after

very careful evaluation.

https://www.city.ac.uk/research/support/integrity-and-ethics/ethics/principles

1.2. Conducting research

HTA involves gathering information and in some cases conducting original research, not just about the science that underlies and supports a health technology, but also about the preferences or values of patients who may use it. Some HTA organisations may explore patient preferences or values directly through qualitative methods. This is particularly relevant for technologies with both, significant desirable and adverse health effects, that must be weighed in decisions about using the technology. From an ethics perspective, research on patient preferences is no different from research on health effects. Therefore, it must conform to the standards for doing research, and be consistent with the principles as laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice.

1.3. Allocating resources

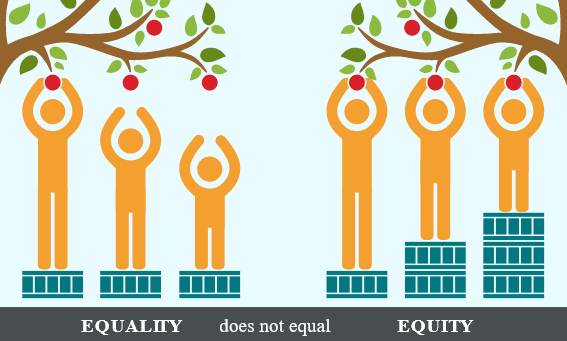

HTA assessments are often used to make decisions about the allocation of resources pertaining to healthcare. When allocating resources, care must be taken to distinguish between equal access and equitable access:

- While the terms equity and equality may sound similar, applying the principle of equal allocation (equal access by all) can lead to an inequitable distribution of health resources and to dramatically different outcomes for those affected, especially if those resources are limited;

- The distinction between equal and equitable access becomes clear by the definition of equity, according to the HTA glossary[1] : ’the fair allocation of resources or treatments among different individuals or groups, such that they each get what they are owed or what they are entitled to. Note: Vertical equity means that the people in the greatest need of services receive the most services, and horizontal equity means that people who have similar needs receive similar services.

- The diagram is a depiction of the difference between equality and equity (source Allies for Reaching Community Health Equity (ARCHE)[2]).

Equal distribution of resources (the same number of crates in this scenario) does not translate to the delivery of fair, non-discriminatory health services. Only by adjusting for the individualised needs of an individual or group and resourcing a different number of crates to each person based on their personal status can disparities in the access to appropriate healthcare (apples in this scenario) within a group be eliminated. Equality does not acknowledge the possibility for a group to be composed of a mixed population of more and less advantaged members. The shortest person in the illustration only has an equal opportunity of attaining an apple when resources are distributed equitably, not equally.

[1] Other, more detailed definition: The use of resource allocation rules based on the distributive justice principle. However, the latter involves various concepts that define these rules more precisely (merit, societal value, the greater good, equal opportunity, equal treatment, priority to the most disadvantaged, standard gamble, etc.). Available at: HtaGlossary.net | equity

[2] ARCHE. Available at: https://healthequity.globalpolicysolutions.org/about-health-equity/

1.4. Considerations for ethical analysis (ETH)

The ethical analysis differs from the other parts of an HTA, i.e. the parts relating to health science, economy and other social science. The ethical understanding may be subjected to empirical studies, e.g. surveys or qualitative, e.g. anthropological studies. Such studies will describe (analytically/theoretically) ethical attitudes, however, they will not determine whether or not they are well-founded or broadly accepted.

It can be discussed if the ethical assessment should result in a concluding attitude to whether the technology in question is ethically justified. An argument against it could be that the HTA should form the basis of a decision of adoption but not as such make the decision. On the other hand, it seems natural that an analysis of ethical problems is followed by a conclusion, which can never be absolute or final because of the dynamic nature of the principles.

It may be useful to draw the decision-makers’ attention to the problem of justice, which is always connected to the use of economic resources in the health care system. The chosen decision is always also a choice of rejecting other possibilities why a clear framework, agreed principles and processes will help making the analysis and decision transparent and acceptable.

Over the past few years there have been major developments in guidance supporting ethical analysis in HTA. Checklists have been developed by academics involved in HTA in order to help structured consideration of ethical issues. These checklists are used by many HTA bodies and are helpful for patient groups as well. The HTA Core Model Version 3.0[1] deserves particular attention; it contains a specific section on Ethical Analysis (pp. 254 – 300), which provides a detailed and structured guide on ethical analysis in HTA, including in ’Appendix Intro-ETH: Ethical considerations within HTA process’ (pp. 406 – 407) a list of questions suggested to be addressed concerning ethical analysis (see also course 5. Ethical, legal and societal issues (ELSI) checklist).