3. Processes and methods

| Site: | EUPATI Open Classroom |

| Course: | HTA Bodies and Principles |

| Book: | 3. Processes and methods |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 1 July 2025, 11:40 AM |

Description

1. Processes and methods

(This section is organised in the form of a book, please follow the blue arrows to navigate through the book or by following the navigation panel on the right side of the page.)

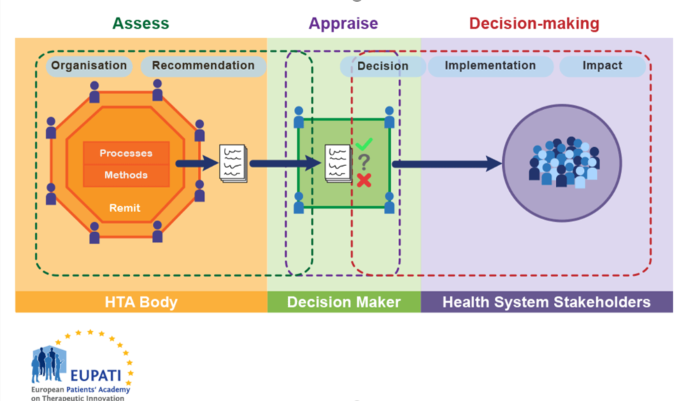

There is great variation in the scope, selection of methods and level of detail in the practice of HTA. In a condensed form the HTA is part of a process which can be characterised by three phases (Figure 1):

- Assessment: Is a phase of collation and critical review of scientific evidence and consideration of clinical and all other factors (economic, legal, ethical, etc.) by the HTA body to make a recommendation.

- Appraisal: Is a phase in the process following the assessment when recommendations on the use of health technology are given. This phase also includes value judgement.

- Decision-making and implementation: based on the appraisal of the recommendation a decision is made, usually by a different body (e.g. a committee appointed by the ministry of health). The technology is implemented in the health system and its impact is monitored.

Figure 1. HTA involvement in the Health System

HTA bodies must choose what information is important for decision makers to have about a technology and how they will gather that information. How an HTA body defines its processes and methods influences the assessments, and they in turn are influenced by the organisation and remit of the HTA body itself.

Most activities involve some form of the following basic steps:

- Identify assessment topics.

- Specify the assessment problems or questions.

- Retrieve available relevant evidence.

- Generate or collect new evidence (as appropriate).

- Appraise/interpret quality of the evidence.

- Integrate/synthesise evidence.

- Formulate findings and recommendations.

- Disseminate findings and recommendations.

- Monitor impact.

Not all HTA bodies conduct all of these steps, and they are not necessarily conducted in this order.

For instance, while understanding the clinical effectiveness of a health technology is generally considered important for decision-makers, some health technologies may have ethical issues associated with their use while others do not. An HTA body must choose if it will apply one standard process to all health technologies, or if it will allow for specific processes for the assessment of each technology individually, based on the relevant information required. In this example, should ethical information be gathered for all technologies under evaluation, or should there be a separate process that provides that information where necessary?

An HTA body may employ a variety of methods. Two of the main types are primary data collection methods and secondary or integrative methods. Primary data methods involve collection of original data, such as from clinical trials and observational studies. Integrative methods, or secondary or synthesis methods, involve combining data or information from existing sources, including from primary data studies. Economic analysis methods can involve one or both. Many HTA bodies rely largely on integrative methods of reviewing and synthesising data (using systematic reviews and meta-analyses) based on existing relevant primary data studies (reported in journal articles or from epidemiological or administrative data sets) to formulate findings. Their evaluations are based on distinguishing between stronger and weaker evidence drawn from available primary data.

Some assessment efforts involve multiple cycles of retrieving/collecting, interpreting, and integrating evidence before completing an assessment.

It is not always possible to conduct an assessment on the basis of the most rigorous types of studies. Real world data can only be collected after a medicine has been put on the market. Indeed, policies often must be made in the absence, or before completion, of definitive studies. Given their varying assessment orientations, resource constraints and other factors, HTA bodies tend to rely on a combination of different methods.

To assess a technology, the HTA body usually requires evidence that addresses multiple issues, including:

- The burden of the illness.

- Projected epidemiological trends of a disease.

- The relative effectiveness of technologies.

- The cost-effectiveness of technologies (note that not all HTA bodies consider cost-effectiveness. Some focus more on added clinical benefit (added value) and budget impact).

- How patients value the outcomes of therapy.

In some cases, an HTA body may answer these questions directly or by commissioning new research. In other cases, they may ask the medicine’s marketing authorisation holder (MAH) to provide the relevant information.

1.1. Assessment

HTA processes pertaining to medicines or devices typically begin with a company submitting a dossier of relevant information to an HTA body.

By default, the dossier includes detailed evidence relating to the safety and efficacy of the new technology as well as ‘added therapeutic benefit’, in other words a comparison of the clinical effectiveness of the new product with the existing standard practice (the comparator).

Some HTA systems in Europe also estimate the impact the new product may have on the health system’s budget (a budget impact evaluation) or the effectiveness of the medicine in comparison to its costs to the system (i.e. a cost-effectiveness analysis or economic evaluation). Not all HTA systems in Europe place the same emphasis on comparative cost-effectiveness analysis, but all focus on the added therapeutic benefit.

The most common components of an application dossier or ‘submission’ are listed below: note that some of these components are more quantitative than others. Equity, legal, and public health aspects may be more qualitative and therefore may be included in the appraisal part of HTA rather than the evaluation part.

- Target patient population: Specification of what population is to be considered for coverage (determined by the full approved indication or a sub-group within that).

- Disease burden: Also known as ‘unmet need’ or ‘therapeutic need’ (while these terms may be used interchangeably, they are often context-related and may carry a different emphasis). It may be a measure of the number of people affected by a particular disease for whom current treatments are inadequate. It may include the number of new diagnoses of a disease, or the costs to society or a government representing those affected. It may also include more qualitative aspects about the burden of disease and current treatments available to patients.

- Medicine description: A description of the medicine, how it works, method of delivery (e.g. injection, tablet), where it is administered to patients, (e.g. in hospital, community, primary care, at home, self-administered), how often, and it's appropriate use in therapy along with other interventions and medicines.

- Clinical efficacy: In medicine, clinical efficacy indicates a positive therapeutic effect. If efficacy is established, an intervention is likely to be at least as good as other available interventions to which it will have been compared. When talking in terms of efficacy versus effectiveness, efficacy measures how well a treatment works in clinical trials or laboratory studies. Effectiveness, on the other hand, relates to how well a treatment works in real-world settings.

- Relative efficacy: The extent to which an intervention does more good than harm under ideal circumstances compared to one or more alternative interventions.

- Clinical effectiveness: Clinical effectiveness is a measure of how well a particular treatment works in real-world settings. It depends on the application of the best knowledge derived from research, clinical knowledge and experience, and patient preferences.

- Relative clinical effectiveness: Can be defined as the extent to which an intervention does more good than harm compared to one or more intervention alternatives for achieving the desired results when provided under the usual circumstances of health care practice.

- Economic evaluation and cost-effectiveness: In the context of pharmacoeconomics, cost effectiveness is studied by looking at the results of different interventions by measuring a single outcome, usually in 'natural' units (for example, life-years gained, deaths avoided, heart attacks avoided, or cases detected). Alternative interventions are then compared in terms of cost per (natural) unit of effectiveness in order to assess how it provides value for money. This helps decision-makers to determine where to allocate limited healthcare resources. Cost effectiveness, however, is only one of a number of criteria that should be used to determine whether or not interventions are made available. Other issues, such as equity, needs, impact on working life, and patient priorities should also be part of the economic evaluation.

- Budget impact: Costs within a particular timeframe and related to a particular healthcare budget rather than a country’s overall budget. This assumes robust data on epidemiology and treatment patterns, along with assumptions of uptake and displacement of current treatments.

- Innovative characteristics: An assessment of whether there are advantages to using the medicine beyond the added clinical benefit (such as convenience to patients of, for example, a different mode of delivery, or other characteristics that may improve adherence to therapy, with resulting improvements in clinical outcomes and / or quality of life).

- Availability of therapeutic alternatives: A description of what else is available to treat the disease. This may or may not be another medicine.

- Equity considerations: An assessment of how adoption of the new therapy might impact measures of fairness within the health system. For example, will the therapy lead to more benefits for people who are socially or economically disadvantaged?

- Public health impact: An examination of how the new therapy might have a broader impact on public health. For example, a new therapy to treat HIV/AIDS may reduce the rate of HIV transmission within a community.

Most HTA bodies have developed guidelines for companies in order to make this process consistent and create fair comparisons. They may be available on the websites of most HTA bodies and can help explain how recommendations/decisions about new medicines are made. However, applicants have to be aware that guidelines vary from country to country and take this into consideration.

Dossiers are assessed by HTA bodies either directly or outsourced. Some HTA bodies conduct independent reviews of the clinical and the economic evidence in order to reduce conflicts of interest. Depending on the HTA organisation, a detailed evaluation of the company’s submission will be carried out rather than conducting an independent review.

1.2. Appraisal

As decision-making regarding reimbursement of a new health technology can be controversial, the best practice approach is to separate evidence assessment from appraisal and also from decision-making. Typically, appraisal committees (often formed from within an HTA body but not necessarily so) that conduct an appraisal will base their recommendations on the outcome of the evidence assessment as well as additional inputs, such as local health policies, values, and patient testimony. In some instances, these committees become part of the decision making.HTA processes generally result in a recommendation to list or not to list the new technology for reimbursement in an insurance-based system (the list includes products with reimbursement from the public health insurance), or recommend it for use in a taxation-based national health service. This may be a listing/recommendation for use of the product under restricted conditions, for example, for a smaller population of patients with more severe illness.

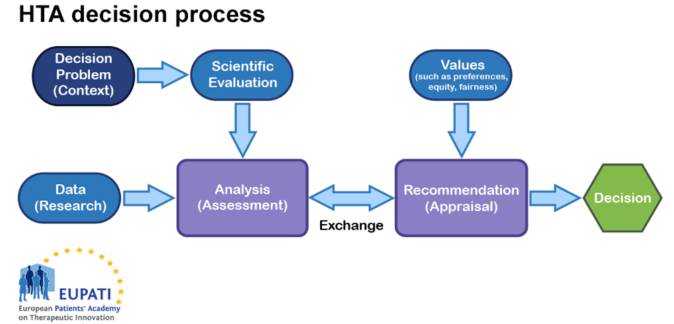

Consider the following diagram:

Figure 1: Diagram of HTA process

Determining whether an intervention will reduce heart attack rates, cause significant side effects, or increase healthcare costs requires judgements about the robustness of evidence. There are always uncertainties in the evidence. Clearly, it is in the best interests of any HTA body to use sound scientific judgment and consistent, transparent approaches that lead to defensible decisions. Given the multidisciplinary nature of HTA, the best approaches from epidemiology, sociology, economics, ethics, law, etc. to support the various analyses are required.

Making a decision, however, requires recognition of what society and patients value. Is it a good thing to reduce heart attack rates? At what cost for the health system or, even broader, to society? Although an individual, or analyst, could create a recommendation, it is generally acknowledged that this would be a weak approach. It is unlikely that an individual is capable of covering all of the perspectives and values of those that ultimately will be affected by the decision.

Good approaches to appraisals will consider multiple perspectives and for this reason, a committee is convened that uses an explicit and transparent process to arrive at a recommendation. This process is often called deliberative appraisal.

Most HTA bodies place great emphasis on the magnitude of (and strength of evidence for) gains in patient-relevant health outcomes seen in well-designed clinical trials with appropriate comparators.

The next most important aspect often comprises economic considerations. Almost all HTA bodies consider budget impact (the total amount that the use of the new medicine will add to the health system budget over a defined period). This should be a net budget figure i.e., one that deducts the savings that might occur elsewhere in the health system as a result of benefits associated with the new medicine (e.g. fewer hospital admissions due to an improved side effect profile) from the expected cost.

For the vast majority of technologies, incremental health benefits come with costs to individuals or the healthcare system, and potential implications for resource allocation by individuals and by societies. It should be considered that health improvements may not yield reductions in expenditures within the healthcare system, but these costs might be at least partially offset by savings in other areas of a society's budget. Very difficult decisions need to be made about how to spend a finite health budget, bearing in mind long-term implications for societal health benefits.

The neutrality of the committee structure must be ensured: – in other words, members of the committee must formally declare any possible conflicts of interest or decline their participation.

Some HTA bodies have adopted an ethical framework that allows for their recommendations to be reviewed by a broader set of stakeholders. This allows for an appeal by the pharmaceutical company, clinicians or patients, who may be unjustly impacted by a flawed, biased or imprecise recommendation.

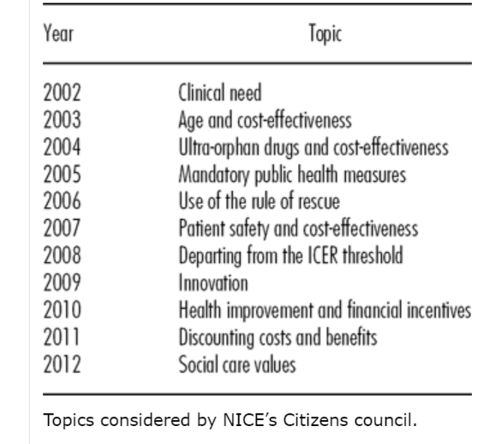

Rarely, HTA bodies seek citizens’ views about challenging aspects of decision-making when deciding priorities in healthcare. For example, in the UK the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has a Citizens’ Council that uses a citizens’ jury approach to provide social value judgements that can inform the NICE appraisal committees. The list below details some of the issues that the Citizens’ Council has advised on.

Topics considered by NICE’s Citizens council.

In some cases, the HTA process will be linked to price negotiations. Negotiating price is one mechanism for governments to provide access to new therapies (that is, finding a way not to say ‘no’). Other variables include restrictions on who may be able to receive the treatment under reimbursement schemes.

1.3. Beyond recommendations

Recommendations about whether a product can be made available within a healthcare system may be viewed as too rigid and not offering flexibility for those who require access to new therapies. Since these recommendations are generally population-focused, they may not allow for exceptions on an individual basis. Rather than a yes/no recommendation, other mechanisms have been applied by HTA that may be more helpful.

- Coverage with evidence development (CED): This can be used to allow access to a promising new product which, at present, has insufficient data supporting either clinical or cost effectiveness. In these circumstances, HTA can recommend use of the medicine, providing there is a formal collection of evidence to resolve those uncertainties while it is being used, for example in a registry. Alternatively, there may be ongoing clinical trials required by regulatory authorities that will deliver additional evidence at some point in the future.

- Price determination: The price of a health technology can have a direct effect on providers and patients’ access to that technology. In some instances, payers may negotiate with the company for a price based on the perceived value of the health technology, especially when the health technology is useful in some cases but not in all. This approach ensures that those providers and patients who need a certain technology have access to it. HTA bodies may or may not be involved in this process. However, value-based pricing presents challenges, as it is difficult to ensure that all aspects of a health technology’s value are adequately considered, for instance, features that are valuable to patients such as convenience of dosage schedules or improved methods of delivery.

- Decision aids and clinical guidelines: The HTA may indicate that the product has most value when used in a particular group of patients or in a particular sequence following other treatment options. To optimise the value, the payer may decide to reimburse the medicine in association with specific clinical guidelines (for prescribers) or specific decision aids (for patients and clinicians). Decision aids are tools for patients and doctors to use evidence to inform an individual decision. They help patients to choose between two treatments that have different risks and benefits. It enables them to have more informed discussions with their doctors about what they value most and to determine which is the best option for them. Read an example from a hospital that shows how such a decision aid might look.

- Health system priority setting and budgets: Methods have evolved to use HTA information to determine what services should be paid for (e.g., to determine what services should be included in universal health coverage). That is, what is the optimal mix that provides value and is affordable to the payer. Find out an explanation and definition of the so-called ‘Programme budgeting and marginal analysis’ employed for these questions

1.4. Decision

Ultimately, the HTA process is intended to support healthcare policy decisions. During this stage of the process, the information gathered and assessed by the HTA body is appraised by decision-makers (e.g. ministries of health, appointed committees, etc.). Although it is assumed decisions are made independently by an HTA body, how decisions are made will have an effect on the HTA process. For example, if decisions can be appealed, then an HTA body may be asked to conduct further analysis. If decisions are made using an expert committee, then an HTA body may have to coordinate the committee or attend its meetings. HTA reports may be held in confidence or made available for public comment.