Trial Participants: Informed Consent, GCP, Patient Involvement

| Site: | EUPATI Open Classroom |

| Course: | Trial Participants' Rights & Obligations |

| Book: | Trial Participants: Informed Consent, GCP, Patient Involvement |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 3 July 2025, 7:53 AM |

Section Overview

- 1. Who Contributes to the Running of a Clinical Trial?

- 2. How Are Clinical Trial Participants Protected?

- 3. How Are Patients Informed About A Trial?

- 4. Patients Can Get Information From Their Healthcare Professionals

- 5. GCP Checklist for Informed Consent

- 6. Protection For Vulnerable Populations

- 7. Other Things To Consider When Dealing With Vulnerable Populations

- 8. Informed Consent in Studies With Participation of Minors

- 9. Patient Involvement in the Informed Consent Process

- 10. Types of Activities Where the Public Can Get Involved

1. Who Contributes to the Running of a Clinical Trial?

(This section is organised in the form of a book, please follow the blue arrows to navigate through the book or by following the navigation panel on the right side of the page.)

Clinical trials are run with contributions from many different organisations such as:

- Research institutes.

- Patient organisations.

- Pharmaceutical companies.

- Governments.

- Universities.

- The trial design.

- Scientific and ethical review procedures.

- Deciding which participants should be included in the trial.

- Finding and recruiting the appropriate participants.

- Guarantee full protection of participants taking part in the clinical trial.

- And more…

2. How Are Clinical Trial Participants Protected?

During the design and before a clinical trial can start, there are several elements that ensure the protection of participants:

Scientific review:

A Clinical Trial Application for the investigational medicinal product (IMP), has to be submitted to the national competent authority of the member state in which the sponsor plans to conduct the clinical trial. They review the documents to ensure the clinical trial is scientifically sound, and the foreseeable risks and inconveniences have been weighed against the anticipated benefit for the individual trial participant.

They also:

- Assess whether the methods to collect data are appropriate.

- Determine whether the most suitable participants are planned to be included.

- Review if the people running the trial are suitably qualified.

- Some review processes also ask for input from patients on the proposed trial design.

Institutional review – Ethics review

A Research Ethics Committee (REC) is there to safeguard the rights, safety, and well-being of all participants in a clinical trial. Its positive opinion is required before a clinical trial can start.

The REC specifically evaluates:

- The relevance of the clinical trial and the trial design.

- Whether the evaluation of the anticipated benefits and risks is satisfactory and whether the conclusions are justified.

- The protocol.

- The suitability of the investigator and supporting staff; (e) the investigator's brochure.

- The quality of the facilities.

- The adequacy and completeness of the written information to be given and the procedure to be followed for the purpose of obtaining informed consent and the justification for the research on persons incapable of giving informed consent.

- The provision for indemnity or compensation in the event of injury or death attributable to a clinical trial.

- Any insurance or indemnity to cover the liability of the investigator and sponsor.

- The amounts and, where appropriate, the arrangements for rewarding or compensating investigators and trial participants and the relevant aspects of any agreement between the sponsor and the site.

- The arrangements for the recruitment of participants:

- Special attention is paid to trials that may include vulnerable participants,

- The REC also assures that there is no coercion or undue influence on the trial participants, and

- Conducts reviews of each ongoing trial at intervals appropriate to the degree of risk to human participants.

Clinical trial guidelines pertaining to the approval of a clinical trial

The Clinical Trials Directive and Regulation harmonises the rules in the EU for the approval of a clinical trial conducted in a member state. As regards NCAs, the details are set out in the Commission Detailed guidance on the request to the competent authorities for authorisation of a clinical trial on a medicinal product for human use, the notification of substantial amendments and the declaration of the end of the trial (CT-1). (here)

With regards to Ethics Committees: Detailed guidance on the application format and documentation to be submitted in an application for an Ethics Committee opinion on the clinical trial on medicinal products for human use. (here)

These guidance:

- Provide public assurance that the rights, safety and well-being of trial participants are protected.

- Establishes principles for the written informed consent documentation:

3. How Are Patients Informed About A Trial?

- Doctors in clinics or hospitals.

- Pharmacies.

- Advertisement.

- Social media.

- Recruitment agencies.

- Pharmaceutical company website.

- Clinical trial website.

- Clinical trial registries (e.g. EUCTR).

- Patient organisations.

The methods used to advertise clinical trials are controlled by legislation.

Advertising is used by pharmaceutical companies and research organisations to recruit for clinical trials, and employ a range of techniques to advertise their trials. In recent years there has been a move away from traditional print based methods, such as posters in doctors’ offices, towards the use of digital tools. These new tools range from dedicated clinical trial recruitment websites, EUCTR (EU clinical trials register), to social media sites.

Trial organisers will also seek potential participants via information provided through many sources such as patient organisations, pharmacies and clinical trial registries.

3.1. Information Used To Recruit Participants For Clinical Trials

Regardless of the route used to reach out to potential participants, all advertisements for trial participants should be included in the CTA (as part of the protocol) to be reviewed by the REC.

The format used to recruit participants in the advertisements can be diverse; however, the advertisements should always:

- Include the contact details for the organisation running the clinical trial.

- State the disease studied and purpose of the trial.

- Give the criteria to determine when a patient can take part in the trial.

- Mention the time needed for completing the trial.

- Promise a good outcome or a cure for the disease the patient has.

- Be coercive, especially when a trial is trying to recruit vulnerable patients, such as those with learning difficulties.

- State that the medicine being tested is safe or that it works.

4. Patients Can Get Information From Their Healthcare Professionals

Healthcare professionals may recommend clinical research as a treatment option for their patients. However a patient may also ask their healthcare professional about clinical research, and whether it might be right for them. Sometimes clinical trials are the only way to provide therapy to patients in serious need. This is still practiced in HIV/AIDS. Early access programs may be too slow or cumbersome, but a trial can save several lives.

In the UK the ‘OK to ask’ campaign is run by the National Institute for Health Research and is aimed at promoting the fact that it’s good to ask about clinical research.

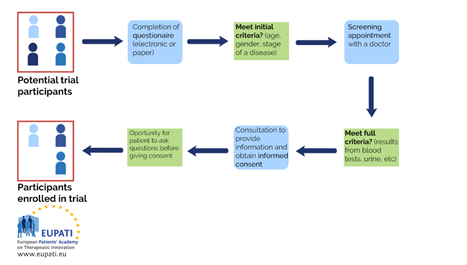

4.1. The Next Steps

When a patient has decided that they would like to enrol in a trial, there are several essential steps that need to be followed before they can ‘sign up’:

- Enrolment - is the process of signing up or recruiting participants into a clinical trial.

- Eligibility - the number of participants enrolled in a study varies greatly depending on the phase of the trial and the trial design. It must be found out whether a participant will meet the requirements outlined in the protocol

(inclusion/exclusion criteria) to join the trial.

- Informed Consent - the participant can then sign the written informed consent after going through the process with a suitably qualified person, usually a member of the research team.

Those who meet the initial requirements are then invited for further screening, usually with a doctor or other healthcare professional directly involved in the trial.

Once the screening determines that the patient meets the inclusion criteria, the patient has a consultation where more and detailed information about the trial is provided, questions can be asked and an informed consent is signed (or refused).

4.2. What is Informed Consent?

There are several procedural safeguards built into the clinical trial process that continue throughout the study to protect the participant.

Informed consent is one of the ways that participants are protected during enrolment into a clinical trial and continues throughout the trial. During this process, potential participants learn the purpose and the potential burdens, risks and benefits of a trial before deciding whether or not they wish to participate.

Informed consent explains the trial to potential participants in understandable language including:

- Purpose.

- Procedures.

- Risks and potential benefits.

- Participant rights including the right to:

- Make an independent decision about participating.

- Leave the study at any time without jeopardising future treatment.

5. GCP Checklist for Informed Consent

Both the informed consent discussion and the written informed consent

form, and any other written information to be provided to patients, should include explanations according to the Guideline for Good Clinical Practice.

The guideline should include explanations of the following:

- The trial involves research.

- Purpose of the trial.

- Trial treatments and probability for random assignment to each treatment.

- Procedures (including invasive) to be followed in the trial.

- Participant’s responsibilities.

- What aspects are experimental.

- Reasonably foreseeable risks or inconveniences to the participant.

- Whether there are expected benefits for the participant or there is no intended clinical benefit.

- Alternative treatments, and their important potential benefits and risks.

- Compensation or treatment available in the event of trial-related injury.

- Anticipated payment, if any, for the participating patient.

- Anticipated expenses, if any, for the participating patient.

- The participation in the trial is voluntary and the person may refuse to participate or withdraw from the trial at any time, without penalty or loss of benefits to which the person is otherwise entitled.

- That the monitor(s), the auditor(s), the REC, and the regulatory authority(ies) will be granted direct access to the participant’s original medical records for verification of clinical trial procedures and/or data, without violating the confidentiality of the participant, to the extent permitted by the applicable laws and regulations and that, by signing a written informed consent form, the participant or the participant’s legally acceptable representative is authorising such access.

- That records identifying the participant will be kept confidential and, to the extent permitted by the applicable laws or regulations, will not be made publicly available. If the results of the trial are published, the participant’s identity will remain confidential.

- The participant or the participant’s legal representative will be informed when information relevant to the participant’s willingness to continue participation in the trial becomes available.

- Contact details to obtain further information regarding the participant’s rights, and whom to contact in the event of trial-related injury.

- Foreseeable circumstances or reasons for which the participation in the trial may be terminated.

6. Protection For Vulnerable Populations

REC’s should safeguard the rights, safety, and well-being of all participants in a clinical trial, thus, they pay special attention to trials that may include vulnerable populations or participants.

According to the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, vulnerable populations

are defined as:

‘Individuals whose willingness to volunteer in a clinical trial may be unduly influenced by the expectation, whether justified or not, of benefits associated with participation or of a retaliatory response associated with participation, or of a retaliatory response from senior members of a hierarchy in case of refusal to participate’.

Some examples of vulnerable participants are:

- Anyone who could be pressured into taking part in the trial by a superior:

- Healthcare staff.

- Members of the armed forces.

- Prisoners.

- Anyone who is particularly vulnerable to coercion:

- Patients with incurable or rare diseases.

- People in nursing homes or the elderly.

- Patients in emergency situations.

- Pregnant women.

- Ethnic minority groups.

- People with special needs or who are incapable of giving consent.

- Refugees or those from developing countries.

- Children.

7. Other Things To Consider When Dealing With Vulnerable Populations

- Researchers should sensitively explore the individual’s abilities and the nature of their special needs. Information about the trial may need to be presented to individuals in a different format. Individuals need to be given plenty of time to think about the trial and ask any questions that they have.

- Children and their parents/legal guardians should be involved in the informed consent process in proportion to the ability of the child to weigh the benefits and risks of the trial. This is known as assent.

- Special care must be taken to make sure elderly people do not feel pressured or coerced into taking part in a trial.

• Prisoners should not be used as participants in a trial unless the trial is specifically looking at topics directly related to prisons or prisoners.

- Care must be taken to avoid healthcare staff feeling pressured to take part in a trial. Assumptions should also not be made about their knowledge of the trial and healthcare staff must be provided with the same detailed information about the trial as other participants.

- Special care must be taken not to overly emphasise the benefits of taking part in a trial in patients who have a rare disease or incurable disease for which there may be few treatment options.

8. Informed Consent in Studies With Participation of Minors

In studies requiring participation of minors, two types of informed consent can be used:

- Signed informed consent from the parent or legal guardians or legally acceptable representatives (LAR).

- Signed informed consent from the minor.

Sample text for parent/legal guardian

Malaria is one of the most common and dangerous diseases in this region. The vaccine that is currently being used is not as good as we would like it to be but there is a new vaccine which may work better. The purpose of this research is to test the new vaccine to see if it protects young children better than the current vaccine.

Example text for minors (12–16 years)

We want to find better ways to prevent malaria before it makes children sick. We have a new vaccine to prevent malaria which we are hoping might be better than the one that is currently being used. In order to find out if it is better we have to test it.

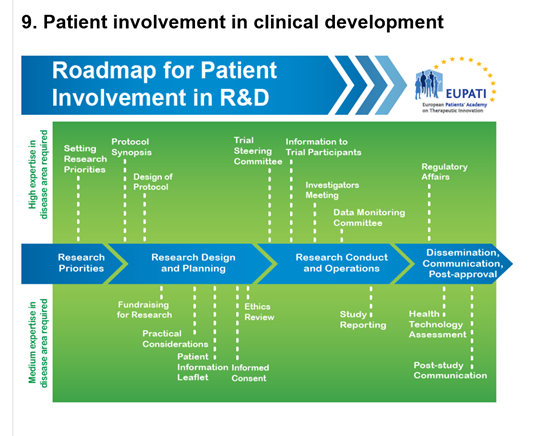

9. Patient Involvement in the Informed Consent Process

Patient representatives can work with the trial organisers to design the informed consent. They can help ensure that the informed consent documentation:

- Is written entirely in understandable and non-technical or scientific language.

- Does not contain persuasive language.

- Explains that participation in the study is entirely voluntary.

- Provides fair perspectives on the possible disadvantages and risks of participation.

- Outlines any direct benefits for the individual and any other beneficial outcomes of the study, including furthering our understanding of the research topic.

10. Types of Activities Where the Public Can Get Involved

- Contributing to patient information leaflets to help recruit and inform people by telling them what they need to know in language they will understand.

- Joining an ethics committee whose job it is to make sure that research carried out respects the dignity, rights, safety and well-being of the people who take part.

- Being part of an advisory group to a research project which helps to develop, support and advise the project.

- Helping to design a questionnaire, thinking through approaches to gaining good quality information from people in a research study.

- Working with others to help communicate research findings to members of the public.

Examples of public involvement in clinical trials:

- Patients and carers contributed significantly to the protocol for a large UK-based multicentre NIHR Health Technology Assessment- funded study (MUSTARDD-PD) researching the management of people with mild dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. People provided constructive ideas around how to raise the subject of dementia with this target population, and suggested alternative wordings to make all the study practicalities much clearer.

- The PURPOSE (Pressure Ulcer Programme of Research) team at the Leeds Clinical Trials Research Unit found the pressure ulcer community to be a seldom heard group due to the lack of an existing service user/carer group and the complex health needs of many people in the community. Therefore, a small network of service users, carers and family members with some personal experience of preventing or living with pressure ulcers was formed.

- The Wales Cancer Trials Unit (WCTU) is strongly committed to public involvement focused on professional working partnerships with the patients. To identify volunteers who are able to contribute effectively and confidently at technically complex meetings, a formal recruitment process was established. Trials staff are involved with the selection and training of new volunteers and the mentoring of existing ones.

A support volunteer’s role includes:

- Recruiting research partners to trials.

- Supporting both research partners and trial managers.

- Reviewing current support systems.

- Identifying development opportunities for research partners.

- Ensuring links with the Involving People network.