Types of Trial Design

| Site: | EUPATI Open Classroom |

| Course: | Clinical Trials and Trial Management |

| Book: | Types of Trial Design |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Tuesday, 20 May 2025, 2:06 PM |

1. Non-randomised Controlled Clinical Trial Designs

In non-randomised controlled trials, participants are allocated into treatment and control arms by the investigator. It is appropriate to use a non-randomised controlled trial design when the act of random allocation may reduce the effectiveness of the intervention.

Non-randomised controlled trials have the potential to study two groups that are not strictly comparable. However, there are different types of controls that can be used in non-randomised trials:

- Control groups can be concurrent controls or historical controls.

2. What is Randomisation?

Randomisation is the process of making something random (assigned by chance). This can be applied in:

- Drawing a random sample of a population.

- Allocating units to different conditions with no order.

There are two components to randomisation:

- The generation of a random sequence.

- Its implementation.

2.1. Randomisation using Stratification

Normally participants would be allocated to a treatment group randomly,

and while this maintains a good overall balance, it can lead to

imbalances within sub-groups. For example if a majority of the

participants who were receiving the medicine happened to be male, or

smokers, the statistical value of the study would be reduced.

The

traditional method to avoid this problem is to stratify participants

according to a number of factors (e.g. age or smokers and non-smokers)

and to use a separate randomisation list for each group. Each

randomisation list would be created such that after every block of a

number of participants, there would be an equal number in each treatment

group.

A stratification factor can either be:

- A categorical covariate - for example: sex, 2 levels, female, male.

- A discretised continuous covariate (i.e. continuous information which has been split into discrete ranges) - for example: age, 3 levels, less than 40 years, 40 to 59, 60 years plus.

2.2. Randomisation Using Cluster Sampling

Cluster sampling is a sampling technique that has been used when ‘natural’ but relatively homogeneous groups are evident in a population. In this technique, the total population is divided into these groups (or clusters) and a simple random sample of the groups is selected. Then the required information is collected within each selected group. This may be done for every element in these groups.

The population within a cluster should ideally be as heterogeneous as possible. Each cluster should be a small-scale representation of the total population.

For example :

- Determine suitable geographical areas (e.g. catchment area, city, country, etc.).

- Randomly choose a number of these geographical areas.

- For each of these chosen geographical areas, choose a proportional sub-sample from the members of the study population in that area.

- Combine these sub-samples to get a sample group.

3. Randomised Controlled Clinical Trial Designs

Randomisation minimises the effect of differences among groups by equally distributing people with particular characteristics among all the trial arms. The researchers do not know which treatment is better. From what is known at the time, any one of the treatments chosen could be of benefit to the participant.

From trial inclusion criteria, equal allocation with regard to gender, age and health status is adopted wherever appropriate. It removes the potential of bias in the allocation of participants and tends to produce comparable groups, however it cannot eliminate accidental bias.

There are two main types of randomised trial designs:

- Parallel group

- Cross-over

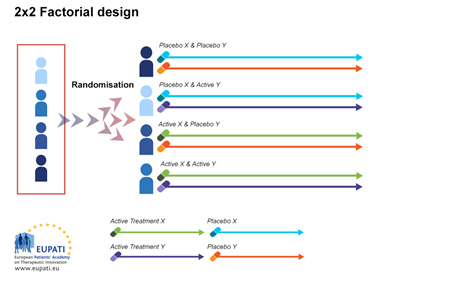

3.1. Factorial Design

In factorial design, it is assumed that there is no interaction between medicines.

Factorial design attempts to evaluate two interventions compared to a control in one trial.

Each participant receives two different treatments: x and y; x and control; y and control; control and control.

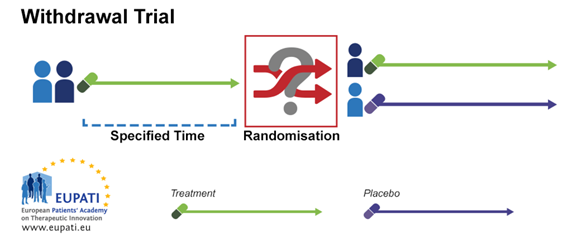

3.2. Withdrawal Trials

In a randomised withdrawal trial, participants receive a test treatment to which they respond for a specified time. At the end of the specified time, participants are randomly assigned to continue treatment with the test treatment or with a placebo (i.e.,

withdrawal of active therapy).

Participants for such a trial could be derived from an organised open single-arm study, from an existing clinical cohort (but usually with a protocol-specified "wash-in" phase to establish the initial on-therapy baseline), from the active arm of a controlled

trial, or from one or both arms of an active control trial. Any difference that emerges between the group receiving continued treatment and the group randomised to placebo would demonstrate the effect of the active treatment.

Withdrawal studies are particularly applicable but not restricted to chronic diseases.

The objectives are:

- To assess response to the dose being stopped or reduced.

- To determine if treatment is still required.

- To discontinue participants in a study that have not responded to the medicine being studied.

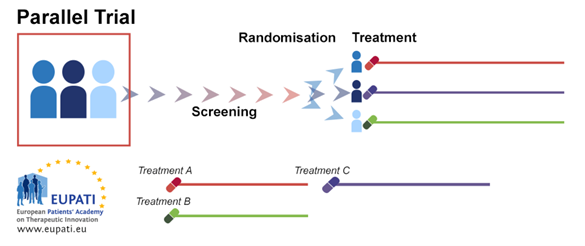

3.3. Parallel Group Trial Design

In parallel group randomisation, participants are randomised to one or two or more arms (groups), there should be an equal number in each arm. Participants receive the same treatment throughout the trial. The results are then compared. Unexplained variability

is attributed to differences between participants. Covariates may explain some participant variables (age, weight, disease severity). The parallel group is the most common design.

Advantages

- Can be applied to almost any disease.

- Any number of groups can be run simultaneously.

- Groups can be in separate locations.

Disadvantages

- High variance brought on by loose connection to control.

- In multiple treatment groups statistics may become challenging.

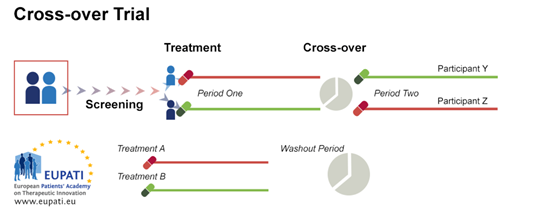

3.4. Cross-over Trial Design

Cross-over randomisation is when participants receive a sequence of different treatments (for example, the candidate compound in the first phase and the comparator/control in the second phase). Each treatment starts at an equivalent point, and each p

serves as their own control. It presents some advantages, such as low variance due to treatment and control being the same participant, and the possibility of including a number of treatments. There must be a washout period between treatments – this

is a period where the participant does not use any treatment. Participants must have a stable and chronic disease. Cross-over trials require fewer participants but for a longer period of time.

Advantages

- Low variance due to participant and control being the same.

- Can include a number of treatments.

Disadvantages

- Requires a long-term illness as treatments are applied one after the other.

- Carry over effects need to be avoided (washout period must be sufficiently long).

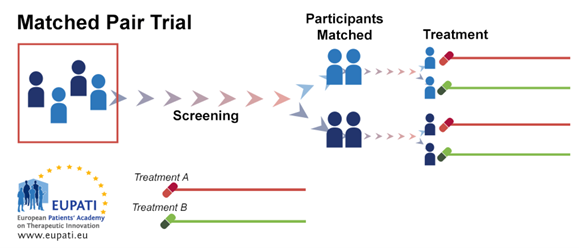

3.5. Matched Pair Trial Design

Randomisation is not always a practical or ethical method of assigning a participant to a comparison group. For example, we cannot assign individuals to wear a seat-belt or not to use it in an attempt to assess the effect of seat-belts in car accidents.

In such situations, the method of matched pair design is widely used. This design can be used when the experiment has only two treatment conditions. In the matched-pair design, participants are first matched in pairs according to certain characteristics.

Then, each member of a pair is randomly assigned to one of the two different study subgroups. This allows comparison between similar study participants who undergo different study procedures.

Matching is typically used in comparative observational studies, in which participants are either self-selected into identifiable groups (e.g. seat-belt wearers and not) or individuals have fixed, pre-determined characteristics that dictate their group

membership (e.g. males and females). The primary advantage of matching is that biases due to baseline group differences are minimised, thereby reducing the variability, and increasing the precision, of the group comparisons.

Advantages

- There is less variability found in results, and it can be applied to most diseases.

Disadvantages

- Based on similarity within the selected groups, the researcher needs awareness of factors that could influence results (confounding variables).

4. Historical Controlled Trial

All participants receive the medicine being studied. The trial results are either compared to:

- the patient’s history (for example a patient suffering from a chronic illness).

- a previous study control group.

5. Designs of Comparison Trials

There are a number of different types of comparison trials possible:

- Superiority to demonstrate that the investigational medicine is better than the control;

- Equivalence to demonstrate that the endpoint measure is similar (no worse, no better) than the control;

- Non-inferiority to demonstrate that the investigational medicine is not worse than the control;

- Dose-response relationship trials to determine various dose parameters, including starting dose and maximum dose.

In an equivalence trial, the statistical test aims at showing that two treatments are not too different in characteristics. These trials are designed to demonstrate that one treatment is as effective as another.

Finally, a non-inferiority trial, is designed to demonstrate that a treatment is at least not (much) worse than a standard treatment. Non-inferiority comparison trials are often used for efficacy studies and the control is a medicine already available to patients.

Dose-response relationship trials are a class of trials that determine an optimal dose (Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) or Optimum Biologic Dose (OBD)) of a specific medicine. The dose response of a medicine is important in pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and toxicology. Dose response studies may be part of larger research to develop new treatments or to supplement existing knowledge of a medicine whose benefits may have already been established.

Dose-response relationship comparison studies investigate:

Typically randomised controlled trials adopt the parallel groups design. Cross-over, cluster and factorial designs are not as common. An analysis of the 616 Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) indexed in PubMed during December 2006 found that 78% were parallel group trials, 16% were cross-over, 2% were split-body, 2% were cluster, and 2% were factorial.